|

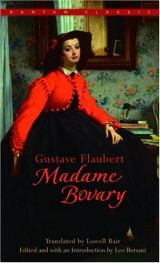

Madame Bovary (Bantam Classics) (平装)

by Gustave Flaubert

| Category:

French Literature, Classic, Fiction |

| Market price: ¥ 88.00

MSL price:

¥ 78.00

[ Shop incentives ]

|

| Stock:

In Stock |

MSL rating:

Good for Gifts Good for Gifts |

MSL Pointer Review:

There are novels of greater structural complexity, or of a broader social canvas, or of more stylistic dash Madame Bovary still stands as the most controlled and beautifully articulated formal masterpiece in the history of fiction.

|

| If you want us to help you with the right titles you're looking for, or to make reading recommendations based on your needs, please contact our consultants. |

|

| |

AllReviews |

1 2   | Total 2 pages 12 items | Total 2 pages 12 items |

|

|

Bruce Kendall (MSL quote), USA

<2007-03-09 00:00>

Making a statement like Madame Bovary is the "greatest" novel ever written would be superfluous. It could be argued that it is the most perfectly written novel in the history of letters and that in creating it, Flaubert mastered the genre. What can't be argued is that it is one of the most influential novels ever written. It changed the face of literature as no other novel has, and has been appreciated and acknowledged by virtually every important novelist who was either Flaubert's contemporary or who came after him.

It's interesting to see the range in opinion that still surrounds this novel. Some of the Readers here at Amazon are morally affronted by the novel's central character, viewing her as something sinister and "unlikeable," and panning the novel for this reason. Such a reaction recalls the negative reviews Bovary engendered soon after its initial publication. It was attacked by many of the authorities of French literature at the time for being ugly and perverse, and for the impression that the novel presented no properly moral frame. These readers didn't "like" Emma much either, and they took their dislike out on her creator.

But this is one of the factors making Madame Bovary "modern". One of the hallmarks of modern novels is that they often portray unsympathetic characters, and Emma certainly falls into this category. How can we as readers "like" a woman who elbows her toddler daughter away from her so forcefully that the child "fell against the chest of drawers, and cut her cheek on the brass curtain-holder." After this pernicious behavior, Emma has a few brief moments of self-castigation and maybe even remorse, but very soon is struck by "what an ugly child" Berthe is. Emma's self-centeredness borders on solipsism. For readers looking for maternal instincts in their female characters or for a depiction of a devoted wife, they had better turn to Pearl S. Buck and The Good Earth, perhaps, rather than to Flaubert.

Much has been made of Flaubert's attempts to remove himself from the narrative, that he was searching for some sort of ultimate objectivity. His narrative technique is much more complex than that, however. It is his employment of a shifting narrative, sometimes objective, sometimes subjective, that again is an indicator of the novel's modernity. At times the narrator is merely reporting events or is involved in providing descriptive details. Yet often the authorial voice makes rather plain how the reader is to look at Emma and her plebeian persona. When she finally succumbs to Rodolphe and thinks she is truly in love, Flaubert becomes downright cynical: " `I've a lover, a lover,' she said to herself again and again, revelling in the thought as if she had attained a second puberty. At last she would know the delights of love, the feverish joys of which she had despaired. She was entering a marvelous world where all was passion, ecstasy, delirium."

Emma is a neurasthenic, in the modern sense, but in the 19th century she would have been said to suffer from hysteria, a mental condition diagnosed primarily in women. When her lovers leave her, she has what amounts to nervous breakdowns. After Rodolphe leaves her she makes herself so sick that she comes near death. Her imagination is much too powerful and too impressionable for her own good. This is part of the reason for Flaubert's oft-repeated quote, "Bovary, c'est moi." Flaubert was a neurasthenic as well and could easily work himself into a swoon as a result of his imaginative flights. There is even conjecture that he may have been, like Dostoevsky, an epileptic, and it is further intimated that this disorder was brought on by nerves, though this may be dubious, medically speaking.

Madame Bovary is not flawless, but it comes awfully close. It is one of the great controlled experiments in the fiction of any era. It even anticipates cinematic technique in many instances, but particularly in the scene at the Agricultural Fair. Note how Flaubert juxtaposes the utterly mundane activities and speeches occurring in the town square with Rodolphe's equally inane seduction of Emma in the empty Council Chamber above the square:

"He took her hand and she did not withdraw it."

"`General Prize!' cried the Chairman.'"

"`Just now, for instance, when I came to call on you...'"

"Monsieur Bizet of Quincampoix."

"`...how could I know that I should escort you here?'"

"Seventy francs!"

"`And I've stayed with you, because I couldn't tear myself away, though I've tried a hundred times.'"

"Manure!"

This is representative Flaubert. With a few deft strokes, he lays the whole absurdity of both the seduction and the provincial's activities bare.

If you have read this book previously and have come away feeling demoralized and even angered, please try reading it again, this time concentrating on the richness of its metaphors, Flaubert's mastery of foreshadowing, symbolism and description. Maybe you will come away with your viewpoint changed. For those who have not yet read this classic of classics, I know that if your mind remains open, you will come away with an appreciation for this master-novelist and for this monumental work.

|

|

|

Lawrance (MSL quote), USA

<2007-03-09 00:00>

When I was teaching World Literature we began class each year reading Gustave Flaubert's Madame Bovary. Unfortunately, this is the one novel that most needs to be read in its original language since Flaubert constructed each sentence of his book with the precision of a poet. As an example of the inherent problems of translation I would prepare a handout with four different versions of the opening paragraphs of Madame Bovary. Each year my students would come to the same conclusion that I had already reached in selecting which version of the book they were to read: Lowell Bair's translation is the best of the lot. It is eminently readable, flowing much better than most of its competitors. Consequently, if you are reading "Madame Bovary" for pleasure or class, this is the translation you want to track down.

Flaubert's controversial novel is the first of the great "fallen women" novels that were written during the Realism period (Anna Karenina and The Awakening being two other classic examples). It is hard to appreciate that this was one of the first novels to offer an unadorned, unromantic portrayal of everyday life and people. For some people it is difficult to enjoy a novel in which they find the "heroine" to be such an unsympathetic figure; certainly the events in Emma Bovary's life have been done to death in soap operas. Still, along with Scarlett O'Hara, you have to consider Emma Bovary one of the archetypal female characters created in the last 200 years of literature. Madame Bovary is one of the greatest and most important novels, right up there with Don Quixote and Ulysses. I just wish I was able to read in it French.

|

|

|

A reader (MSL quote), USA

<2007-03-09 00:00>

...that is to say : this is one the books that can't be translated, becauses it uses all potentialities of french language. Those who admire in this book the cruelty and truth of the psychological portraits mustn't forget that Flaubert's dream was to write a "book about nothing, that would be held only by the force of the style". The story didn't interest him and in his correspondance you see how he got bored while writing it. Personnaly I don't like this kind of "feminine life in the country and loss of illusions that is to entail" but the style is just amazing. Proust said that Flaubert had "a grammatical genius". That's why anyone who can read french might throw his english version. Also, don't be obsessed by the famous "Madame Bovary, c'est moi". Flaubert wrote this book to get rid of his romantic tendancies : hence this mix of sympathy and deep cruelty about the stupidity of his heroin. This cruelty is reinforced by the use of the "focalisation interne" (when the writer writes from the point of view of the character) and the perfect neutrality : we live from the inside Emma's dreams and feel how ridiculous they are, and then, from the outside, we see them being slowly destructed. Read this masterpiece, and focus your attention on the style, and the construction (otherwise the book has little interest!)

|

|

|

Donald Mitchell (MSL quote) , USA

<2007-03-09 00:00>

Depending on your perspective, this book is hopelessly dated and has little relevance to today, is an important step forward in the French novel, or is a classic depiction of tragedy in the Greek tradition. You should decide which perspective is most meaningful to you in determining whether you should read the book or not.

The story of the younger Madame Bovary (her mother-in-law is the other) is presented in the context of people whose illusions exceed their reality. Eventually, reality catches up with them. In the case of Emma Bovary, these illusions are mostly tied up in the notion that romantic relationships will make life wonderful and that love conquers all. She meets a young doctor of limited potential and marries with little thought. Soon, she finds him unbearable. The only time she is happy is when the two attend a ball at a chateaux put on by some of the nobility (the beautiful people of that time). She has a crisis of spirit and becomes depressed. To help, he moves to another town where life may be better for her. She has a daughter, but takes no interest in her. Other men attract her, and she falls for each one who pays attention to her in a romantic style. Clearly, she is in love with romance. Adultery is not rewarded, and she has a breakdown when one lover leaves her. Recovering, she takes on a younger lover she can dominate. This, too, works badly and she becomes reckless in her pursuit of pleasure. In the process, she takes to being reckless in other ways and brings financial ruin to herself and her family. The book ends in tragedy.

Here is the case for this being dated and irrelevant for today. A modern woman would usually not be trapped in such a way. She would separate from or divorce the husband she grew to detest, and make a new life. She would be able to earn a decent living, and would not be discouraged from raising a child alone. So the story would probably not happen now. In addition, the psychological aspects of her dilemma would be portrayed in terms of an inner struggle reflecting our knowledge today of psychology, rather than as a visual struggle followed mostly by a camera lens in this novel. The third difference is that the shallow stultifying people exalted by the society would be of little interest today. You find few novels about boring people in small towns in rural areas.

The case for the book as important in French literature is varied. The writing is very fine, and will continue to attract those who love the French language forever. This is a rare novel for its day in that it focused on a heroine who was neither noble by class nor noble in spirit. The book clearly makes more of an exploration into psychology than all but a few earlier French novels. The story itself was a shocking one in its day, for its focus on immoral behavior and the author's failure to overtly condemn that behavior. Emma pays the price, as Hollywood would require, but there is no sermonizing against her. So this book is a breakthrough in the modern novel in its shift in focus and tone to a personal pedestrian level.

From a third perspective, this book is a modern update of the classic Green tragedy in which all-too human characters struggle against a remorseless fate and are destroyed in the process. But we see their humanity and are moved by it. Emma's character is a hopeless romantic is established early. To be a hopeless romantic in a world where no one else she meets is condemns her to disappointment. She also seems to have some form of mental illness that makes it hard for her to deal with setbacks. But her optimism that somehow things will work out makes her appealing to us, and makes us wish for her success. When she does not succeed, we grieve with her family. Flaubert makes many references to fate in the novel, so it seems likely that this reading was intended.

My own view is that the modern reader who is not a scholar of French literature can only enjoy this book from the third perspective. If you do, there are many subtle ironies relative to the times and places in the novel that you will appreciate, as well. The ultimate ascendence of the careful, unimaginative pharmacist provides many of these. The ultimate fate of Madame Bovary's daughter, Berthe, is another. Be sure to look for these ironies among the details of these prosaic lives. The book positively teems with them.

If you are interested in perspectives two or three, I suggest you read and savor this fine classic. If you want something that keeps pace with modern times, manners, mores and knowledge, avoid this book!

If you do decide to read Madame Bovary, after you are done be sure to consider in what elements of your life you are filled with illusions that do not correspond to reality. We all have vague hopes that "when" we have "it" (whatever "it" is), life will be perfect. These illusions are often doomed to be shattered. Let your joy come from the seeking of worthy goals, instead! What worthy goals speak deeply into your heart and mind? In this way, you can overcome the misconceptions that stall your personal progress.

|

|

|

Bayliss (MSL quote), USA

<2007-03-09 00:00>

What surprised me about rereading Madame Bovary was not how much I enjoyed it, but how much many of my AP English students enjoyed it. Unlike other "older" novels, this one held much more allure for its feminine perspective and for its many "modern" themes. I think fellow reviewer Mitchell does an excellent job going over some different perspectives we can appreciate, but I'd like to amplify his last perspective: young people do find the book startlingly modern. What other "classic" protagonist is so bold in seeking personal pleasure over convention? As for the writing, I wish I could read it in French - often I got the feeling that the writing would be even better in the original, but to Flaubert's credit (and the translator's), its literary qualities are still intact. We had many lively debates regarding Emma's morality and her selfishness -- many in the class felt sorry for Charles. Students who are good readers enjoy Madame Bovary more than other more moralistic tales like the Scarlet Letter often read in the same course. They find Flaubert much "hipper" than his American counterpart Hawthorne.

For anyone who has been saving the reading of this book, wait no more - even though Flaubert claims not to have been that interested in plot or character, the book is still a lively and compelling read on every front. One of my all time favorites.

|

|

|

A reader (MSL quote), USA

<2007-03-09 00:00>

Let's begin with Nabokov's "Lectures on Literature," where he introduces Madame Bovary as follows: "The book is concerned with adultery and contains situations and allusions that shocked the prudish philistine government of Napoleon III. Indeed, the novel was actually tried in a court of justice for obscenity. Just imagine that. As if the work of an artist could ever be obscene." Written over a five-year period, "Madame Bovary" was published serially in a magazine in 1856 where, despite editorial attempts to purge it of offensive material, it was cited for "offenses against morality and religion." Fortunately, Flaubert won his case and Madame Bovary remains to this day one of the masterpieces of French and world literature. Indeed, in Nabokov's view, the novel's influence is notable: "Without Flaubert, there would have been no Marcel Proust in France, no James Joyce in Ireland. Chekhov in Russia would not have been quite Chekhov."

The story of Emma Bovary is well known and uncomplicated. Set in the provincial towns of Tostes and Yonville (it is subtitled Patterns of Provincial Life), with adulterous interludes in Rouen, Madame Bovary narrates the life of Charles Bovary and Emma Rouault. Charles, an "officier de sante" - a licensed medical practitioner without a medical degree - meets Emma while tending to her injured father. Charles is married at that time to the first Madame Bovary, also called Madame Dubuc, a widow and thin, ugly woman who dominates the mild-mannered Charles from the very beginning. "It was his wife (Madame Dubuc) who ruled: in front of company he had to say certain things and not others, he had to eat fish on Friday, dress the way she wanted, obey her when she ordered him to dun nonpaying patients. She opened his mail, watched his every move, and listened through the thinness of the wall when there were women in his office."

When Madame Dubuc dies a few short years after their marriage, it appears that Charles is fortunate, for he is not only freed from the shrewish oppression of his wife, but enabled to court and marry the beautiful Emma. It is the eight-year marriage of Charles and Emma that embodies the tale of Madame Bovary, a tale marked by Emma's ennui, her dissatisfaction with the unsatisfied yearnings of bourgeois marriage in a small provincial town, her steadily growing sensual insatiability, her adulteries with a series of men. It is this marriage, too, that gives us one of literature's great cuckolds, Charles Bovary.

Madame Bovary has often been described as a realistic novel and, insofar as it tells a seemingly ordinary tale of sensual longing and adultery while, at the same, time depicting characters and sensibilities typical of bourgeois, philistine rural France during the reign of Louis Phillipe, it is grimly realistic. It is also, however, a deeply psychological novel, one in which Flaubert brilliantly probes the feelings, the sensations, the romantic longings and dreamscapes of Emma Bovary. Above all, Madame Bovary is the apogee of the French novel prior to Proust's Parnassian achievement, a novel whose poetic language and artistic rendering transcend mere narrative and elevate Flaubert's work to that of high literary art, a novel for the ages. Read it in the original French if you can; if not, then read it in Frances Steegmuller's outstanding English translation.

|

|

|

Robert Moore (MSL quote) , USA

<2007-03-09 00:00>

This is not among my few favorite novels, but no one who is sensitive to great literature can fail to see the brilliance of this work. In doing a bit of background work, I made the following discoveries:

Virtually every French writer of the late 19th acknowledged Flaubert as their model. In England, Thomas Hardy essentially tried to write Flaubertian novels in an English rural context. Later in England, D. H. Lawrence explicitly wrote novels that were polemical to Flaubert, so that he wrote in reaction against Madame Bovary. In Russia, Tolstoy decided to write his own version of the story of Emma Bovary, ANNA KARENINA. In the 20th century, James Joyce - who was proud of how few writers he had studied - confessed that he had read virtually every line of Flaubert and himself tried to carry to the furthest extreme the Flaubertian dictum of art for arts sake. And this is merely the tip of the proverbial iceberg.

Is this the most influential novel ever written? I honestly don't know, but if one wanted to construct a case for that assertion, a very, very powerful one could be made.

|

|

|

A reader (MSL quote), USA

<2007-03-09 00:00>

Madame Bovary is considered a masterpiece by historical context, but it's easy to see why it holds up well today. As much a social comedy as a personal tragedy, it taps into the same kinds of emotions and desires that have shaped Western society for the past 150 years - ambition, lust, escapism. It is a depressing novel whose heroine is so thoroughly unsympathetic that you read it to find out if she gets what she deserves.

Emma Rouault's misfortune is that she grew up with unrealistic expectations about life. As a girl, she indulged herself in romantic novels and developed maudlin and almost fantastical notions of what love and marriage must be like. She accepts the proposal of a socially awkward widower and doctor named Charles Bovary, even though she does not seem to have much genuine love for him. In accordance with her fantasies, their wedding is straight out of a fairy tale.

The fairy tale doesn't last long. Emma soon finds herself bored by her husband's spartan lifestyle and annoyed by his occasional professional ineptitude. Shameful of what she perceives to be her low social status as a country doctor's wife, she is attracted by the glamor of big cities and high society she reads about in the fashionable magazines. She dutifully takes care of her household, but she is selfish, temperamental, and mean to her servants and her baby daughter. What's pathetic about her is that she wants to experience the kind of love she's read about in her books, but her personality is so antithetical to what love is that she will never be able to understand or appreciate it in its purest form.

After the Bovarys move to a small rural town called Yonville, Emma's beauty and charm attract the flirtatious attentions of several men in town, including two with whom she succumbs to adultery: Leon, a young law clerk, with whom she carries on an affair in the nearby city of Rouen under the guise of taking piano lessons; and the suave but sleazy Rodolphe who, impudently (and correctly) calculating her husband to be a naive dullard, uses her and throws her away like the tramp that she is. In the course of her webs of deceipt and her taste for expensive, fashionable things, she drives herself and her husband into irreparable debt with morbidly tragic conclusions.

The characterization of the Yonville townsfolk is so rich that whole other novels could be written about them. In particular there is the garrulous pharmacist Monsieur Homais, a neo-Voltaire type of character who disdains the clergy and has faith in science and a morality based on common sense. Such characterization provides a comic counterbalance to Emma's majestically tragic figure; I've seen the same kind of thing in novels by Balzac and Thomas Hardy, where the unwashed masses are always there in the background, reassuring us that the world, on average, goes on the way it always has even while the main characters are front and center playing out their little dramas.

|

|

|

Luis Luque (MSL quote) , USA

<2007-03-09 00:00>

And the short answer to the question above, is "Nothing." So many great reviewers and critics agree that this is one of the greatest masterpieces of literature that I finally had to see for myself. I was definitely not disappointed.

Even in translation, it is easy to notice the extreme care that Flaubert put into his choices of mood and tone, metaphors, analogies, descriptions, dialogue, his characters' interior monologue, even the length of sentences, paragraphs and chapters. And his plot is not only perfectly paced, but keeps giving you interesting tidbits right till the very end.

I don't even begin to compare it with Anna Karenina or The Scarlet Letter. In terms of sheer entertainment value, Madame Bovary wins hands down. While it doesn't provide the scope or the psychological analysis of Tolstoy's masterpiece, I found it less demanding and far more enjoyable. No, the characters aren't as three-dimensional as Tolstoy's, but neither are there reams of pages full of farming, hunting and local politics with which to get bored.

If you're looking for the first real modern novel, look no further. Not only is it the first, but it is also one of the very best.

|

|

|

A reader (MSL quote), USA

<2007-03-09 00:00>

150 years on, this reads as freshly as anything published this year. The point, surely, is not whether Emma Bovary is a good woman, or a bad mother, as some reviewers seem to think. What we get is a woman who is entirely human. Her ultimately fatal desires are believable, her weaknesses as common today as they ever were.

A post-modern Emma Bovary would divorce, take the kid, and juggle childcare with a career in casting or magazine journalism. Flaubert's heroine had no such options. Her dreams manifested themselves in the futile search for a transforming love - a goal as seductive today as ever.

Just as Cervantes wrote Don Quixote in part as satire on the literary tastes of the day, Flaubert takes aim at the unrealistic romance novels of his time. His antidote is a story of such realism we recognise every character and every human foible. The sexual descriptions, while not explicit in a modern sense, are still remarkably frank, their power transparent.

The author most similar, in my view, is Flaubert's English contemporary Thomas Hardy. I am a huge fan of Hardy, but none of his heroes, not Jude nor the Mayor of Casterbridge nor even Tess comes to us as intimately as the beautiful, ardent, bored and ultimately wasted Emma B.

|

|

|

|

1 2   | Total 2 pages 12 items | Total 2 pages 12 items |

|

|

|

|

|

|