|

|

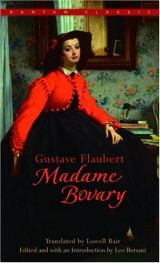

Madame Bovary (Bantam Classics) (Paperback)

by Gustave Flaubert

| Category:

French Literature, Classic, Fiction |

| Market price: ¥ 88.00

MSL price:

¥ 78.00

[ Shop incentives ]

|

| Stock:

In Stock |

MSL rating:

Good for Gifts Good for Gifts |

MSL Pointer Review:

There are novels of greater structural complexity, or of a broader social canvas, or of more stylistic dash Madame Bovary still stands as the most controlled and beautifully articulated formal masterpiece in the history of fiction.

|

| If you want us to help you with the right titles you're looking for, or to make reading recommendations based on your needs, please contact our consultants. |

Detail |

Author |

Description |

Excerpt |

Reviews |

|

|

|

Author: Gustave Flaubert

Publisher: Bantam Classics

Pub. in: June, 1982

ISBN: 0553213415

Pages: 512

Measurements: 6.9 x 3.9 x 1 inches

Origin of product: USA

Order code: BA00790

Other information: ISBN-13: 978-0553213416

|

|

Rate this product:

|

|

- Awards & Credential -

Novel by Gustave Flaubert, published in two volumes in 1857. It ushered in a new age of realism in literature. |

|

- MSL Picks -

In this masterpiece of French literature, Gustave Flaubert tells the tale of Emma Bovary, née Roualt, an incurably romantic woman who finds herself trapped in an unsatisfactory marriage in a prosaic bourgeois French village, Yonville-l'Abbaye.

Her attempts to escape the tedium of her life through a series of adulterous affairs are thwarted by the reality that the men she chooses to love are shallow and self-centered and thus are unable to love anyone but themselves.

In love with a love that can never be and dreadfully overstretched financially, Emma finds herself caught in a downward spiral that can only end in tragedy.

Part of the difficulty, and the pleasure, of reading Madame Bovary comes from the fact the Flaubert refuses to embed his narrative with a moral matrix; he refuses, at least explicitly, to tell the reader, what, if any, moral lesson he should draw from the text.

It is this lack of moral viewpoint that made Madame Bovary shocking to Flaubert's contemporaries, so much so that Flaubert found himself taken to court for the novel's offenses to public and religious decency. Although today's readers will find no such apparent scandals in the book, they will still be challenged to make sense of both Emma and her story.

It is quite common to see Emma Bovary as silly, extravagant and much too romantically inclined. An avid consumer of romantic literature (a habit into which the heroine was indoctrinated in her convent school upbringing), Emma has made the morbid mistake of buying into the notion of romantic love in its fullest sense, and the mortal mistake of believing she can reach its fulfillment in her own life.

As such, Emma Bovary becomes a tragic figure of almost mythic proportion. Far from being foolish and self-indulgent, Emma is the victim of her own fecund imagination. A lesser woman would have been satisfied in the constrained world Emma inhabits, a world of sewing and teas and parties. But Emma is possessed of both splendid passions and tremendous energy; an artist and a rebel in her challenge to the priorities and ideals of her age.

Madame Bovary is an unusual novel in the sense that it has given its name to its own psychological condition: bovarysme, the condition in which we delude ourselves as to who and what we really are and as to life's potential to fulfill.

In this sense, Madame Bovary becomes the story of one woman's faulty perception of reality. In an early version of the novel, Flaubert included a scene at the ball at La Vaubyessard in which Emma is seen looking out at the landscape surrounding the house through colored panes of glass, a scene clearly meant as a representation of Emma's projection onto the world of an illusory and faulty model of reality.

Emma cannot, or will not, see the world as it is, since she is constantly imposing onto it, and herself, the criteria of romantic literature. Flaubert has thus written a supremely romantic novel about the dangers of reading supremely romantic novels!

Romantics, Flaubert seems to be saying, have no reasonable hope of ever seeing their fondest dreams come to fruition.

This is, indeed, a recurrent pattern in the novel: Emma dreams of one thing but gets something else entirely. Marriage, motherhood, and ultimately, adultery, all fall short of Emma's expectations and she appears to be a woman doomed to one disappointment after another.

Although Emma believes her marriage will fulfill her romantic expectations, Charles certainly fails to live up to Emma's hopes, and even Rodolphe, with his expensive riding boots, gloves and substantial income is eventually considered coarse and vulgar by Emma. Léon, the very essence of the young, romantic artist, leaves Emma when he is made premier clerc, and Emma finds she much come to the realization that even adultery contains "toutes les platitudes du mariage."

The foregoing certainly begs the question: are Emma's expectations too high or is life fundamentally deficient?

The society portrayed in Madame Bovary is one stratified in terms of class, and this is a book about the bourgeoisie, a portrait of class in the process of finding and defining itself and its role in society.

The novel is filled with scenes of buying and selling and even personal relationships fall under the sway of financial considerations.

What is particularly notable about Emma is her extravagance: she spares no thought for expense and consumes far beyond her means. Rejecting good economic management, thrift and hard work, Emma dedicates herself to style extraordinaire and lavishes expensive presents on her "man of the moment."

The world described in Madame Bovary is an extremely enclosed and restricted one and images of entrapment are abundant throughout the book. Emma's first marital home is described as "trop étroite;" her marriage to Charles is likened to "l'ardillon pointu de cette courroie complexe qui la bouclait de tous les côtes."

These restrictive images clearly demonstrate how confining Emma finds her world. Trapped in the dusty and damp home with its "éternel jardin," the highly imaginative Emma sees no escape.

It is interesting to note that when Emma does attempt to escape the confines of femininity, society and marriage through adultery, many of the scenes take place al fresco. (The first act of adultery with Rodolphe takes place in a forest and her later relationship with Léon contains a scene on a river.)

Later scenes, however, reveal the degradation inherent in Emma's acts and she finds herself confined to bedrooms that are sorely reminiscent of the restrictions of her married life. The fiacre ride with Léon in Rouen, in particular, is anticipatory of entrapment. For Emma, adultery eventually becomes as much of a prison as is marriage and family life.

Another recurrent image is that of the window. This can be interpreted as Emma's desire for escape or as a reaffirmation of her entrapment and powerlessness. The window opens onto a space of which poor Emma can only sit and dream; it serves as a frame for both her dissatisfaction and her fantasies.

In order to enjoy Madame Bovary to the fullest extent, it must be read in the original French. This is an absolute for Flaubert was an author who made full use of the potential offered by his native tongue. Although many translations are superb, nothing can match the original French in its poetic prose and lush descriptions.

Many interpretations of this wonderful and timeless novel are possible and all, no doubt, hold some validity. Therein lies the book's genius. Of one thing, though, we have no doubt: luscious Emma Bovary was, indeed, a victim. Whether of herself or of a repressive society matters little.

(Quoting from an American reader)

Target readers:

Readers who love ramantic fiction, or French Literature or just classic novels.

|

|

The great French novelist was born in Rouen in 1821, son of a distinguished surgeon. He studied law briefly, but in 1844 he was struck with epilepsy - it was the first of a series of violent fits that filled Flaubert’s life with apprehension and drove him to lead a hermit’s life. Having been attracted to literature at an early age, he soon turned his entire attention to writing. His first novel, Madame Bovary, won instant fame upon his publication in 1857: Flaubert was sued for “immorality,” but was later acquitted.

An avid traveler, his fundamentally romantic nature reveling in the exotic, Flaubert went to Tunisia to research his second novel, Salammbo (1862). Both Salammbo and The Sentimental Education (1869) were poorly received, and Flaubert’s genius was not publicly recognized until his masterful Three Tales (1877). Among his literary peers, his reputation was extraordinary, and he formed lasting friendships with Turgenev, George Sand, and the Goncourt brothers.

Despite his reputation as a master of realists, he was not fundamentally a realistic novelist. Flaubert’s aim was to achieve a rigidly objective form of art, presented in the most perfect form. His obsession with his craft is legendary: he could work seven hours a day, many days on end, on a single page, trying to attune his style to his ideal of balanced harmony, seeking always le mot juste.

In 1875 Flaubert sacrificed his modest fortune to help his niece, Caroline, and as a result his last years were marked by financial worry and bitter isolation. He died suddenly in May, 1880, leaving his last work, Bouvard and Pécuchet unfinished.

|

|

From the Publisher

This exquisite novel tells the story of one of the most compelling heroines in modern literature - Emma Bovary. Unhappily married to a devoted, clumsy provincial doctor, Emma revolts against the ordinariness of her life by pursuing voluptuous dreams of ecstasy and love. But her sensuous and sentimental desires lead her only to suffering corruption and downfall. A brilliant psychological portrait, Madame Bovary searingly depicts the human mind in search of transcendence. Who is Madame Bovary? Flaubert's answer to this question was superb: "Madame Bovary, c'est moi." Acclaimed as a masterpiece upon its publication in 1857, the work catapulted Flaubert to the ranks of the world's greatest novelists. This volume, with its fine translation by Lowell Bair, a perceptive introduction by Leo Bersani, and a complete supplement of essays and critical comments, is the indispensable Madame Bovary.

|

Part One

We were in study hall when the headmaster walked in, followed by a new boy not wearing a school uniform, and by a janitor carrying a large desk. Those who were sleeping awoke, and we all stood up as though interrupting our work.

The headmaster motioned us to sit down, then turned to the teacher and said softly, "Monsieur Roger, I'm placing this pupil in your care. He'll begin in the eighth grade, but if his work and conduct are good enough, he'll be promoted to where he ought to be at his age."

The newcomer hung back in the corner behind the door, so that we could hardly see him. He was a country boy of about fifteen, taller than any of us. He wore his hair cut straight across the forehead, like a cantor in a village church, and he had a gentle, bewildered look. Although his shoulders were not broad, his green jacket with black buttons was apparently too tight under the arms, and the slits of its cuffs revealed red wrists accustomed to being bare. His legs, sheathed in blue stockings, protruded from his yellowish trousers, which were pulled up tight by a pair of suspenders. He wore heavy, unpolished, hobnailed shoes.

We began to recite our lessons. He concentrated all his attention on them, as though listening to a sermon, not daring even to cross his legs or lean on his elbow, and when the bell rang at two o'clock the teacher had to tell him to line up with the rest of us.

When we entered a classroom we always tossed our caps on the floor, to free our hands; as soon as we crossed the threshold we would throw them under the bench so hard that they struck the wall and raised a cloud of dust; this was "the way it should be done."

But the new boy either failed to notice this maneuver or was too shy to perform it himself, for he was still holding his cap on his lap at the end of the prayer. It was a head-gear of composite nature, combining elements of the busby, the lancer cap, the round hat, the otter-skin cap and the cotton nightcap - one of those wretched things whose mute ugliness has great depths of expression, like an idiot's face. Egg-shaped and stiffened by whalebone, it began with three rounded bands, followed by alternating diamond-shaped patches of velvet and rabbit fur separated by a red stripe, and finally there was a kind of bag terminating in a cardboard-lined polygon covered with complicated braid. A network of gold wire was attached to the top of this polygon by a long, extremely thin cord, forming a kind of tassel. The cap was new; its visor was shiny.

"Stand up," said the teacher.

He stood up; his cap fell. The whole class began to laugh.

He bent down and picked it up. A boy beside him knocked it down again with his elbow; he picked it up once again.

"Will you please put your helmet away?" said the teacher, a witty man.

A loud burst of laughter from the other pupils threw the poor boy into such a state of confusion that he did not know whether to hold his cap in his hand, leave it on the floor or put it on his head. He sat down again and put it back on his lap.

"Stand up," said the teacher, "and tell me your name."

The new boy mumbled something unintelligible.

"Say it again!"

The same mumbled syllables came from his lips again, drowned out by the jeers of the class.

"Louder!" cried the teacher. "Louder!"

With desperate determination the new boy opened his enormous mouth and, as though calling someone, shouted this word at the top of his lungs: "Charbovari!"

This instantly touched off an uproar which rose in a crescendo of shrill exclamations, shrieks, barks, stamping of feet and repeated shouts of "Charbovari! Charbovari!" Then it subsided into isolated notes, but it was a long time before it died down completely; it kept coming back to life in fits and starts along a row of desks where a stifled laugh would occasionally explode like a half-spent firecracker.

A shower of penalties gradually restored order in the classroom, however, and the teacher, having managed to understand Charles Bovary's name after making him repeat it, spell it out and read it to him, immediately ordered the poor devil to sit on the dunce's seat at the foot of the rostrum. He began to walk over to it, then stopped short.

"What are you looking for?" asked the teacher.

"My ca -" the new boy said timidly, glancing around uneasily."

The whole class will copy five hundred lines!" Like Neptune's "Quos ego" in the Aeneid, this furious exclamation checked the outbreak of a new storm. "Keep quiet!" continued the teacher indignantly, mopping his forehead with a handkerchief he had taken from his toque. "As for you," he said to the new boy, "you will write out 'Ridiculus sum' twenty times in all tenses." He added, in a gentler tone, "Don't worry, you'll find your cap: it hasn't been stolen."

Everything became calm again. Heads bent over notebooks, and for the next two hours the new boy's conduct was exemplary, despite the spitballs, shot from the nib of a pen, that occasionally splattered against his face. He merely wiped himself with his hand each time this happened, then continued to sit motionless, with his eyes lowered.

That evening, in study hall, he took sleeveguards from his desk, put his things in order and carefully ruled his paper. We saw him working conscientiously, looking up all the words in the dictionary and taking great pains with everything he did. It was no doubt because of this display of effort that he was not placed in a lower grade, for, while he had a passable knowledge of grammatical rules, his style was without elegance. He had begun to study Latin with his village priest, since his parents, to save money, had postponed sending him off to school as long as possible.

His father, Monsieur Charles-Denis-Bartholomé Bovary, had once been an assistant surgeon in the army. Forced to leave the service in 1812 for corrupt practices with regard to conscription, he had taken advantage of his masculine charms to pick up a dowry of sixty thousand francs being offered to him in the person of a hosier's daughter who had fallen in love with his appearance. He was a handsome, boastful man who liked to rattle his spurs; his side whiskers joined his mustache, his fingers were always adorned with rings and he wore bright-colored clothes. He had the look of a pimp and the affable exuberance of a traveling salesman. He lived on his wife's money for the first two or three years of their marriage, eating well, getting up late, smoking big porcelain pipes, staying out every night to see a show and spending a great deal of time in cafés. His father-in-law died and left very little; indignant at this, he "went into the textile business" and lost some money, then he moved to the country, where he intended to "build up a going concern." But since he knew little more about farming than he did about calico, since he rode his horses instead of sending them off to work in the fields, drank his bottled cider instead of selling it, ate the finest poultry in his barnyard and greased his hunting shoes with the fat of his pigs, he soon realized that he would do well to give up all thought of business endeavor.

So for two hundred francs a year he rented a residence that was half farm and half gentleman's estate, on the border between Picardy and the Caux region of Normandy. Melancholy, consumed with regrets, cursing heaven, envious of everyone, he withdrew into seclusion at the age of forty-five, disgusted with mankind, he said, and resolved to live in peace.

His wife had been mad about him in the beginning; she had loved him with a boundless servility that made him even more indifferent to her. She had been vivacious, expansive and brimming over with affection in her youth, but as she grew older she became peevish, nagging and nervous, like sour wine turning to vinegar. She had suffered so much at first without complaining, watching him run after every village strumpet in sight and having him come home to her every night, satiated and stinking of alcohol, after carousing in a score of ill-famed establishments! Then her pride rebelled; she withdrew into herself, swallowing her rage with a mute stoicism which she maintained until her death. She was always busy with domestic and financial matters. She was constantly going to see lawyers or the judge, remembering when notes were due and obtaining renewals; and at home she spent all her time ironing, sewing, washing, supervising the workmen and settling the itemized bills they presented to her, while Monsieur, totally unconcerned with everything and continually sinking into a sullen drowsiness from which he roused himself only to make disagreeable remarks to her, sat smoking beside the fire and spitting into the ashes.

When she had a child it had to be placed in the care of a wet-nurse. The boy was pampered like a prince when he came back to live with them. His mother fed him on jam and candied fruit; his father let him run barefoot and even carried his philosophical pretensions to the point of saying that he might as well go naked, like a young animal. In opposition to his wife's maternal tendencies, he had a certain virile ideal of childhood, and he tried to form his son in accordance with it. He wanted him to be raised harshly, Spartan-style, in order to give him a sturdy constitution. He sent him to bed without a fire, taught him to take hearty swigs of rum and to jeer at religious processions. But, placid by nature, the child showed little response to his father's efforts. His mother kept him tied to her apron-strings; she cut out cardboard figures for him, told him stories and talked to him in endless monologues full of melancholy gaiety and wheedling chatter. In the isolation of her life she transferred all her shattered, abandoned ambitions to her child. She dreamed of high positions, she saw him already grown...

|

|

| View all 12 comments |

Bruce Kendall (MSL quote), USA

<2007-03-09 00:00>

Making a statement like Madame Bovary is the "greatest" novel ever written would be superfluous. It could be argued that it is the most perfectly written novel in the history of letters and that in creating it, Flaubert mastered the genre. What can't be argued is that it is one of the most influential novels ever written. It changed the face of literature as no other novel has, and has been appreciated and acknowledged by virtually every important novelist who was either Flaubert's contemporary or who came after him.

It's interesting to see the range in opinion that still surrounds this novel. Some of the Readers here at Amazon are morally affronted by the novel's central character, viewing her as something sinister and "unlikeable," and panning the novel for this reason. Such a reaction recalls the negative reviews Bovary engendered soon after its initial publication. It was attacked by many of the authorities of French literature at the time for being ugly and perverse, and for the impression that the novel presented no properly moral frame. These readers didn't "like" Emma much either, and they took their dislike out on her creator.

But this is one of the factors making Madame Bovary "modern". One of the hallmarks of modern novels is that they often portray unsympathetic characters, and Emma certainly falls into this category. How can we as readers "like" a woman who elbows her toddler daughter away from her so forcefully that the child "fell against the chest of drawers, and cut her cheek on the brass curtain-holder." After this pernicious behavior, Emma has a few brief moments of self-castigation and maybe even remorse, but very soon is struck by "what an ugly child" Berthe is. Emma's self-centeredness borders on solipsism. For readers looking for maternal instincts in their female characters or for a depiction of a devoted wife, they had better turn to Pearl S. Buck and The Good Earth, perhaps, rather than to Flaubert.

Much has been made of Flaubert's attempts to remove himself from the narrative, that he was searching for some sort of ultimate objectivity. His narrative technique is much more complex than that, however. It is his employment of a shifting narrative, sometimes objective, sometimes subjective, that again is an indicator of the novel's modernity. At times the narrator is merely reporting events or is involved in providing descriptive details. Yet often the authorial voice makes rather plain how the reader is to look at Emma and her plebeian persona. When she finally succumbs to Rodolphe and thinks she is truly in love, Flaubert becomes downright cynical: " `I've a lover, a lover,' she said to herself again and again, revelling in the thought as if she had attained a second puberty. At last she would know the delights of love, the feverish joys of which she had despaired. She was entering a marvelous world where all was passion, ecstasy, delirium."

Emma is a neurasthenic, in the modern sense, but in the 19th century she would have been said to suffer from hysteria, a mental condition diagnosed primarily in women. When her lovers leave her, she has what amounts to nervous breakdowns. After Rodolphe leaves her she makes herself so sick that she comes near death. Her imagination is much too powerful and too impressionable for her own good. This is part of the reason for Flaubert's oft-repeated quote, "Bovary, c'est moi." Flaubert was a neurasthenic as well and could easily work himself into a swoon as a result of his imaginative flights. There is even conjecture that he may have been, like Dostoevsky, an epileptic, and it is further intimated that this disorder was brought on by nerves, though this may be dubious, medically speaking.

Madame Bovary is not flawless, but it comes awfully close. It is one of the great controlled experiments in the fiction of any era. It even anticipates cinematic technique in many instances, but particularly in the scene at the Agricultural Fair. Note how Flaubert juxtaposes the utterly mundane activities and speeches occurring in the town square with Rodolphe's equally inane seduction of Emma in the empty Council Chamber above the square:

"He took her hand and she did not withdraw it."

"`General Prize!' cried the Chairman.'"

"`Just now, for instance, when I came to call on you...'"

"Monsieur Bizet of Quincampoix."

"`...how could I know that I should escort you here?'"

"Seventy francs!"

"`And I've stayed with you, because I couldn't tear myself away, though I've tried a hundred times.'"

"Manure!"

This is representative Flaubert. With a few deft strokes, he lays the whole absurdity of both the seduction and the provincial's activities bare.

If you have read this book previously and have come away feeling demoralized and even angered, please try reading it again, this time concentrating on the richness of its metaphors, Flaubert's mastery of foreshadowing, symbolism and description. Maybe you will come away with your viewpoint changed. For those who have not yet read this classic of classics, I know that if your mind remains open, you will come away with an appreciation for this master-novelist and for this monumental work.

|

Lawrance (MSL quote), USA

<2007-03-09 00:00>

When I was teaching World Literature we began class each year reading Gustave Flaubert's Madame Bovary. Unfortunately, this is the one novel that most needs to be read in its original language since Flaubert constructed each sentence of his book with the precision of a poet. As an example of the inherent problems of translation I would prepare a handout with four different versions of the opening paragraphs of Madame Bovary. Each year my students would come to the same conclusion that I had already reached in selecting which version of the book they were to read: Lowell Bair's translation is the best of the lot. It is eminently readable, flowing much better than most of its competitors. Consequently, if you are reading "Madame Bovary" for pleasure or class, this is the translation you want to track down.

Flaubert's controversial novel is the first of the great "fallen women" novels that were written during the Realism period (Anna Karenina and The Awakening being two other classic examples). It is hard to appreciate that this was one of the first novels to offer an unadorned, unromantic portrayal of everyday life and people. For some people it is difficult to enjoy a novel in which they find the "heroine" to be such an unsympathetic figure; certainly the events in Emma Bovary's life have been done to death in soap operas. Still, along with Scarlett O'Hara, you have to consider Emma Bovary one of the archetypal female characters created in the last 200 years of literature. Madame Bovary is one of the greatest and most important novels, right up there with Don Quixote and Ulysses. I just wish I was able to read in it French.

|

A reader (MSL quote), USA

<2007-03-09 00:00>

...that is to say : this is one the books that can't be translated, becauses it uses all potentialities of french language. Those who admire in this book the cruelty and truth of the psychological portraits mustn't forget that Flaubert's dream was to write a "book about nothing, that would be held only by the force of the style". The story didn't interest him and in his correspondance you see how he got bored while writing it. Personnaly I don't like this kind of "feminine life in the country and loss of illusions that is to entail" but the style is just amazing. Proust said that Flaubert had "a grammatical genius". That's why anyone who can read french might throw his english version. Also, don't be obsessed by the famous "Madame Bovary, c'est moi". Flaubert wrote this book to get rid of his romantic tendancies : hence this mix of sympathy and deep cruelty about the stupidity of his heroin. This cruelty is reinforced by the use of the "focalisation interne" (when the writer writes from the point of view of the character) and the perfect neutrality : we live from the inside Emma's dreams and feel how ridiculous they are, and then, from the outside, we see them being slowly destructed. Read this masterpiece, and focus your attention on the style, and the construction (otherwise the book has little interest!)

|

Donald Mitchell (MSL quote) , USA

<2007-03-09 00:00>

Depending on your perspective, this book is hopelessly dated and has little relevance to today, is an important step forward in the French novel, or is a classic depiction of tragedy in the Greek tradition. You should decide which perspective is most meaningful to you in determining whether you should read the book or not.

The story of the younger Madame Bovary (her mother-in-law is the other) is presented in the context of people whose illusions exceed their reality. Eventually, reality catches up with them. In the case of Emma Bovary, these illusions are mostly tied up in the notion that romantic relationships will make life wonderful and that love conquers all. She meets a young doctor of limited potential and marries with little thought. Soon, she finds him unbearable. The only time she is happy is when the two attend a ball at a chateaux put on by some of the nobility (the beautiful people of that time). She has a crisis of spirit and becomes depressed. To help, he moves to another town where life may be better for her. She has a daughter, but takes no interest in her. Other men attract her, and she falls for each one who pays attention to her in a romantic style. Clearly, she is in love with romance. Adultery is not rewarded, and she has a breakdown when one lover leaves her. Recovering, she takes on a younger lover she can dominate. This, too, works badly and she becomes reckless in her pursuit of pleasure. In the process, she takes to being reckless in other ways and brings financial ruin to herself and her family. The book ends in tragedy.

Here is the case for this being dated and irrelevant for today. A modern woman would usually not be trapped in such a way. She would separate from or divorce the husband she grew to detest, and make a new life. She would be able to earn a decent living, and would not be discouraged from raising a child alone. So the story would probably not happen now. In addition, the psychological aspects of her dilemma would be portrayed in terms of an inner struggle reflecting our knowledge today of psychology, rather than as a visual struggle followed mostly by a camera lens in this novel. The third difference is that the shallow stultifying people exalted by the society would be of little interest today. You find few novels about boring people in small towns in rural areas.

The case for the book as important in French literature is varied. The writing is very fine, and will continue to attract those who love the French language forever. This is a rare novel for its day in that it focused on a heroine who was neither noble by class nor noble in spirit. The book clearly makes more of an exploration into psychology than all but a few earlier French novels. The story itself was a shocking one in its day, for its focus on immoral behavior and the author's failure to overtly condemn that behavior. Emma pays the price, as Hollywood would require, but there is no sermonizing against her. So this book is a breakthrough in the modern novel in its shift in focus and tone to a personal pedestrian level.

From a third perspective, this book is a modern update of the classic Green tragedy in which all-too human characters struggle against a remorseless fate and are destroyed in the process. But we see their humanity and are moved by it. Emma's character is a hopeless romantic is established early. To be a hopeless romantic in a world where no one else she meets is condemns her to disappointment. She also seems to have some form of mental illness that makes it hard for her to deal with setbacks. But her optimism that somehow things will work out makes her appealing to us, and makes us wish for her success. When she does not succeed, we grieve with her family. Flaubert makes many references to fate in the novel, so it seems likely that this reading was intended.

My own view is that the modern reader who is not a scholar of French literature can only enjoy this book from the third perspective. If you do, there are many subtle ironies relative to the times and places in the novel that you will appreciate, as well. The ultimate ascendence of the careful, unimaginative pharmacist provides many of these. The ultimate fate of Madame Bovary's daughter, Berthe, is another. Be sure to look for these ironies among the details of these prosaic lives. The book positively teems with them.

If you are interested in perspectives two or three, I suggest you read and savor this fine classic. If you want something that keeps pace with modern times, manners, mores and knowledge, avoid this book!

If you do decide to read Madame Bovary, after you are done be sure to consider in what elements of your life you are filled with illusions that do not correspond to reality. We all have vague hopes that "when" we have "it" (whatever "it" is), life will be perfect. These illusions are often doomed to be shattered. Let your joy come from the seeking of worthy goals, instead! What worthy goals speak deeply into your heart and mind? In this way, you can overcome the misconceptions that stall your personal progress.

|

View all 12 comments |

|

|

|

|