|

|

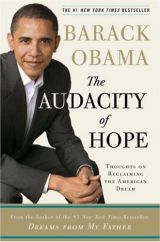

The Audacity of Hope: Thoughts on Reclaiming the American Dream (Hardcover)

by Barack Obama

| Category:

American Dream, American society, Non-fiction |

| Market price: ¥ 278.00

MSL price:

¥ 218.00

[ Shop incentives ]

|

| Stock:

In Stock |

|

|

MSL rating:

Good for Gifts Good for Gifts |

| MSL Pointer Review:

Optimistic, refreshing and beautifully written, The Audacity of Hope is a very American introduction to Senator Obama and his stance on current issues. |

| If you want us to help you with the right titles you're looking for, or to make reading recommendations based on your needs, please contact our consultants. |

Detail |

Author |

Description |

Excerpt |

Reviews |

|

|

|

Author: Barack Obama

Publisher: Crown

Pub. in: October, 2006

ISBN: 0307237699

Pages: 384

Measurements: 9.5 x 6.5 x 1.4 inches

Origin of product: USA

Order code: BA00627

Other information: ISBN-13: 978-0307237699

|

|

Rate this product:

|

|

- Awards & Credential -

The #1 New York Times Bestseller from the author of another #1 New York Times Bestseller Dreams from My Father. This book ranks #6 in books on Amazon.com out of millions as of January 16, 2007. |

|

- MSL Picks -

The Audacity of Hope is a personal introduction to Senator Obama: an auto-biography of his life from childhood to present, his family and his views and approach to politics based on personal experience, education and involvement which is diverse, well rounded, and extensive - he is both studied in law (he has been a practicing lawyer), American history, constitutional law, and foreign policy.

Senator Obama leaves no stones unturned as to where he stands on all major issues from faith, economics, environment, foreign and domestic policy, war (he voted against invading Iraq on very reasoned points of inherent, long-range repercussions). Although he has his feet firmly planted in liberal, democratic policies, he is not stuck in single point-of-view politics: he respects all points of view and considerations; he believes that policies on both sides of the isle can and do have merit and his bi-partisan voting record demonstrates this.

He is a Christian, yet firmly believes in the sanctity and rights of all religions and the non- religious alike and that no particular religion should be infused into politics as the torch-bearer of personal morality legislation in America- separation of church and state is a must, yet he also believes that religious points of view and voice have a place at the political round-table.

Senator Obama feels that abortion is a woman's personal business and choice and he proffers that the best approach to prevention is universal sex education, rights to birth control, moral guidance including abstinence as a choice, but without dogma and derision. And he believes that all politicians, especially liberals, should be more frank about openly discussing their moral viewpoints and "... values in ways that don't appear calculated or phony." (p.63)

Indeed, we have seen what vote scamming of the Christian Right with hypocritical, unfulfilled promises has wrought and it's enough to make one puke, yet we can also be thankful that the most extreme of those anti-constitutional rights wish-lists have not been fulfilled. Check-out David Kuo's new book "Tempting Faith" for an indept Christian "insider's" expose' on vote scamming of the Evanelical Christian Right by the Bush Admin.

Over-all, I found Senator Obama's approach to life and political points of view to be polarity busting, pragmatic, fair and balanced - a refreshing break from the status quo. I should think that people from all walks of life and persuasions can find much to appreciate in his thoughtful and reasoned approach to all matters at hand. The index is extensive and helpful in referencing his life experiences, politics and view points.

(From quoting Patrick, USA)

Target readers:

General readers.

|

|

- Better with -

Better with

America Alone: The End of the World as We Know It

:

|

|

Barack Obama is the junior U.S. senator from Illinois. He is the author of the #1 New York Times Bestseller Dreams from My Father. He lives in Chicago with his wife, Michelle, and two daughters.

|

|

From Publisher

"A government that truly represents these Americans - that truly serves these Americans - will require a different kind of politics. That politics will need to reflect our lives as they are actually lived. It won’t be pre-packaged, ready to pull off the shelf. It will have to be constructed from the best of our traditions and will have to account for the darker aspects of our past. We will need to understand just how we got to this place, this land of warring factions and tribal hatreds. And we’ll need to remind ourselves, despite all our differences, just how much we share: common hopes, common dreams, a bond that will not break." - from The Audacity of Hope

In July 2004, Barack Obama electrified the Democratic National Convention with an address that spoke to Americans across the political spectrum. One phrase in particular anchored itself in listeners’ minds, a reminder that for all the discord and struggle to be found in our history as a nation, we have always been guided by a dogged optimism in the future, or what Senator Obama called "the audacity of hope."

Now, in The Audacity of Hope, Senator Obama calls for a different brand of politics - a politics for those weary of bitter partisanship and alienated by the "endless clash of armies" we see in congress and on the campaign trail; a politics rooted in the faith, inclusiveness, and nobility of spirit at the heart of "our improbable experiment in democracy." He explores those forces - from the fear of losing to the perpetual need to raise money to the power of the media - that can stifle even the best-intentioned politician. He also writes, with surprising intimacy and self-deprecating humor, about settling in as a senator, seeking to balance the demands of public service and family life, and his own deepening religious commitment.

At the heart of this book is Senator Obama’s vision of how we can move beyond our divisions to tackle concrete problems. He examines the growing economic insecurity of American families, the racial and religious tensions within the body politic, and the transnational threats - from terrorism to pandemic - that gather beyond our shores. And he grapples with the role that faith plays in a democracy - where it is vital and where it must never intrude. Underlying his stories about family, friends, members of the Senate, even the president, is a vigorous search for connection: the foundation for a radically hopeful political consensus.

A senator and a lawyer, a professor and a father, a Christian and a skeptic, and above all a student of history and human nature, Senator Obama has written a book of transforming power. Only by returning to the principles that gave birth to our Constitution, he says, can Americans repair a political process that is broken, and restore to working order a government that has fallen dangerously out of touch with millions of ordinary Americans. Those Americans are out there, he writes - “waiting for Republicans and Democrats to catch up with them.”

|

Prologue

It’s been almost ten years since I first ran for political office. I was thirty-five at the time, four years out of law school, recently married, and generally impatient with life. A seat in the Illinois legislature had opened up, and several friends suggested that I run, thinking that my work as a civil rights lawyer, and contacts from my days as a community organizer, would make me a viable candidate. After discussing it with my wife, I entered the race and proceeded to do what every first-time candidate does: I talked to anyone who would listen. I went to block club meetings and church socials, beauty shops and barbershops. If two guys were standing on a corner, I would cross the street to hand them campaign literature. And everywhere I went, I’d get some version of the same two questions.

"Where’d you get that funny name?"

And then: "You seem like a nice enough guy. Why do you want to go into something dirty and nasty like politics?"

I was familiar with the question, a variant on the questions asked of me years earlier, when I’d first arrived in Chicago to work in low-income neighborhoods. It signaled a cynicism not simply with politics but with the very notion of a public life, a cynicism that - at least in the South Side neighborhoods I sought to represent - had been nourished by a generation of broken promises. In response, I would usually smile and nod and say that I understood the skepticism, but that there was - and always had been - another tradition to politics, a tradition that stretched from the days of the country’s founding to the glory of the civil rights movement, a tradition based on the simple idea that we have a stake in one another, and that what binds us together is greater than what drives us apart, and that if enough people believe in the truth of that proposition and act on it, then we might not solve every problem, but we can get something meaningful done. It was a pretty convincing speech, I thought. And although I’m not sure that the people who heard me deliver it were similarly impressed, enough of them appreciated my earnestness and youthful swagger that I made it to the Illinois legislature.

Six years later, when I decided to run for the United States Senate, I wasn’t so sure of myself.

By all appearances, my choice of careers seemed to have worked out. After spending my two terms during which I labored in the minority, Democrats had gained control of the state senate, and I had subsequently passed a slew of bills, from reforms of the Illinois death penalty system to an expansion of the state’s health program for kids. I had continued to teach at the University of Chicago Law School, a job I enjoyed, and was frequently invited to speak around town. I had preserved my independence, my good name, and my marriage, all of which, statistically speaking, had been placed at risk the moment I set foot in the state capital.

But the years had also taken their toll. Some of it was just a function of my getting older, I suppose, for if you are paying attention, each successive year will make you more intimately acquainted with all of your flaws - the blind spots, the recurring habits of thought that may be genetic or may be environmental, but that will almost certainly worsen with time, as surely as the hitch in your walk turns to pain in your hip. In me, one of those flaws had proven to be a chronic restlessness; an inability to appreciate, no matter how well things were going, those blessings that were right there in front of me. It’s a flaw that is endemic to modern life, I think - endemic, too, in the American character - and one that is nowhere more evident than in the field of politics. Whether politics actually encourages the trait or simply attracts those who possess it is unclear. Lyndon Johnson, who knew much about both politics and restlessness, once said that every man is trying to either live up to his father’s expectations or make up for his father’s mistakes, and I suppose that may explain my particular malady as well as anything else.

In any event, it was as a consequence of that restlessness that I decided to challenge a sitting Democratic incumbent for his congressional seat in the 2000 election cycle. It was an ill-considered race, and I lost badly - the sort of drubbing that awakens you to the fact that life is not obliged to work out as you'd planned. A year and a half later, the scars of that loss sufficiently healed, I had lunch with a media consultant who had been encouraging me for some time to run for statewide office. As it happened, the lunch was scheduled for late September 2001.

"You realize, don’t you, that the political dynamics have changed," he said as he picked at his salad.

"What do you mean?" I asked, knowing full well what he meant. We both looked down at the newspaper beside him. There, on the front page, was Osama bin Laden.

"Hell of a thing, isn’t it?" he said, shaking his head. "Really bad luck. You can’t change your name, of course. Voters are suspicious of that kind of thing. Maybe if you were at the start of your career, you know, you could use a nickname or something. But now... "His voice trailed off and he shrugged apologetically before signaling the waiter to bring us the check.

I suspected he was right, and that realization ate away at me. For the first time in my career, I began to experience the envy of seeing younger politicians succeed where I had failed, moving into higher offices, getting more things done. The pleasures of politics - the adrenaline of debate, the animal warmth of shaking hands and plunging into a crowd - began to pale against the meaner tasks of the job: the begging for money, the long drives home after the banquet had run two hours longer than scheduled, the bad food and stale air and clipped phone conversations with a wife who had stuck by me so far but was pretty fed up with raising our children alone and was beginning to question my priorities. Even the legislative work, the policy-making that had gotten me to run in the first place, began to feel too incremental, too removed from the larger battles - over taxes, security, health care, and jobs - that were being waged on a national stage. I began to harbor doubts about the path I had chosen; I began feeling the way I imagine an actor or athlete must feel when, after years of commitment to a particular dream, after years of waiting tables between auditions or scratching out hits in the minor leagues, he realizes that he’s gone just about as far as talent or fortune will take him. The dream will not happen, and he now faces the choice of accepting this fact like a grown-up and moving on to more sensible pursuits, or refusing the truth and ending up bitter, quarrelsome, and slightly pathetic.

Denial, anger, bargaining, despair - I’m not sure I went through all the stages prescribed by the experts. At some point, though, I arrived at acceptance - of my limits, and, in a way, my mortality. I refocused on my work in the state senate and took satisfaction from the reforms and initiatives that my position afforded. I spent more time at home, and watched my daughters grow, and properly cherished my wife, and thought about my long-term financial obligations. I exercised, and read novels, and came to appreciate how the earth rotated around the sun and the seasons came and went without any particular exertions on my part.

And it was this acceptance, I think, that allowed me to come up with the thoroughly cockeyed idea of running for the United States Senate. An up-or-out strategy was how I described it to my wife, one last shot to test out my ideas before I settled into a calmer, more stable, and better-paying existence. And she - perhaps more out of pity than conviction - agreed to this one last race, though she also suggested that given the orderly life she preferred for our family, I shouldn’t necessarily count on her vote.

I let her take comfort in the long odds against me. The Republican incumbent, Peter Fitzgerald, had spent $19 million of his personal wealth to unseat the previous senator, Carol Moseley Braun. He wasn’t widely popular; in fact he didn’t really seem to enjoy politics all that much. But he still had unlimited money in his family, as well as a genuine integrity that had earned him grudging respect from the voters.

For a time Carol Moseley Braun reappeared, back from an ambassadorship in New Zealand and with thoughts of trying to reclaim her old seat; her possible candidacy put my own plans on hold. When she decided to run for the presidency instead, everyone else started looking at the Senate race. By the time Fitzgerald announced he would not seek reelection, I was staring at six primary opponents, including the sitting state comptroller; a businessman worth hundreds of millions of dollars; Chicago Mayor Richard Daley’s former chief of staff; and a black, female health-care professional who the smart money assumed would split the black vote and doom whatever slim chances I’d had in the first place.

I didn’t care. Freed from worry by low expectations, my credibility bolstered by several helpful endorsements, I threw myself into the race with an energy and joy that I thought I had lost. I hired four staffers, all of them smart, in their twenties or early thirties, and suitably cheap. We found a small office, printed letterhead, installed phone lines and several computers. Four or five hours a day, I called major Democratic donors and tried to get my calls returned. I held press conferences to which nobody came. |

|

| View all 16 comments |

Jonathan Alter, Newsweek.com (MSL quote), USA

<2007-01-16 00:00>

He is one of the best writers to enter modern politics. |

Michiko Katutani (New York Times) (MSL quote) , USA

<2007-01-16 00:00>

"[Barack Obama] is that rare politician who can actually write - and write movingly and genuinely about himself... In these pages he often speaks to the reader as if he were an old friend from back in the day, salting policy recommendations with colorful asides about the absurdities of political life... [He] strives in these pages to ground his policy thinking in simple common sense... while articulating these venomous pre-election days, but also in these increasingly polarized and polarizing times."

|

Los Angles Times (MSL quote), USA

<2007-01-16 00:00>

"[Few] on the partisan landscape can discuss the word "hope" in a political context and be regarded as the least bit sincere. Obama is such a man, and he proves it by employing a fresh and buoyant vocabulary to scrub away some of the toxins from contemporary political debate. Those polling categories that presume to define the vast chasm between us do not, Obama reminds us, add up to the sum of our concerns or hint at where our hearts otherwise intersect... Obama advances ordinary words like "empathy", "humility", "grace" and "balance" into the extraordinary context of 2006's hyper-agitated partisan politics. The effect is not only refreshing but also hopeful... As you might anticipate from a former civil lawyer and a university lecturer on constitutional law, Obama writes convincingly about race as well as the lofty place the Constitution holds in American life... He writes tenderly about family and knowingly about faith. Readers, no matter what their party affiliation, may experience the oddly uplifting sensation of comparing the everyday contemptuous view of politics that circulates so widely in our civic conversations with the practical idealism set down by this slender, smiling, 45-year-old former sate legislator who is included on virtually every credible list of future presidential contenders. |

A reader (MSL quote), USA

<2007-01-16 00:00>

Barack Obama, considered by many as a contender for the Democratic nomination, has written a fantastic treatise of his ideas about government, the issues facing our country and the American people themselves. One may not always agree with his opinions, but his approach is hard to disagree with. Obama says that we have so much more to unite us than divide us and calls for public discourse that reflects this reality. He seeks a liberal, compassionate policy that never strays from our values, but in fact, represents them. Both when you disagree with him and when you agree with him, he still makes you ponder first, before he attempts to persuade you. He puts out all the evidence, rather than skipping right to his conclusions - though, when they come, they are powerful. In addition, he makes it personal - he tells you why he feels the way he does, so you get perspective on his perspective. Obama is an extremely refreshing addition to the political debate not because his policies are different from the norm - in fact, they generally fit in right with the Democratic party, though a bit more moderate. What is special in Obama is his seemingly unusual faith in the process. Presidents often can say a lot about various issues, but they cannot cover everything they will face in their presidency. What matters a lot for all important people is their outlook - how they think and what, at their core, they believe. And for these characteristics, Obama passes the test with flying colors.

|

View all 16 comments |

|

|

|

|