|

|

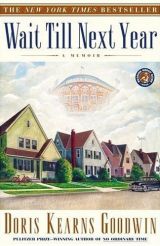

Wait Till Next Year: A Memoir (Paperback)

by Doris Kearns Goodwin

| Category:

Memoir, Baseball |

| Market price: ¥ 168.00

MSL price:

¥ 148.00

[ Shop incentives ]

|

| Stock:

Pre-order item, lead time 3-7 weeks upon payment [ COD term does not apply to pre-order items ] |

MSL rating:

Good for Gifts Good for Gifts |

| MSL Pointer Review:

A magnificent tale of growing up, a vivid and delightful memoir of a Brooklyn childhood with a love for baseball. |

| If you want us to help you with the right titles you're looking for, or to make reading recommendations based on your needs, please contact our consultants. |

Detail |

Author |

Description |

Excerpt |

Reviews |

|

|

|

Author: Doris Kearns Goodwin

Publisher: Simon & Schuster

Pub. in: June, 1998

ISBN: 0684847957

Pages: 272

Measurements: 8.5 x 5.5 x 0.7 inches

Origin of product: USA

Order code: BA00633

Other information: ISBN-13: 978-0684847955

|

|

Rate this product:

|

|

- Awards & Credential -

The New York Times Bestseller. |

|

- MSL Picks -

To appreciate the quality of this work, consider for a moment the many ways it could have been manhandled. Too much emphasis upon the Dodgers-Yankees-Giants rivalry of the 1950's would have produced a superficial sketch of 1950's baseball, already more than adequately recounted by David Halberstam, among others. Worse, the author might have adopted an "Angela's Ashes" style of dramatizing a childhood that was in fact comfortable middle class living in post-War Long Island. Or much worse, we might have gotten yet another "growing up Catholic" Gothic tale of terror.

Doris Kearns Goodwin found the proper balance, so that the uniqueness of this work rests not upon her description of baseball, the Eisenhower administration, or American Catholicism, but upon a surprisingly intimate portrait of her childhood that reveals more of her personal mysteries than perhaps she herself realizes. The cultural institutions she highlights-particularly baseball-are in reality the metaphors by which she discovers herself and invites us to share in those discoveries. That the author is an American public treasure-an author of note, the congenial presidential scholar who shares titillating historical gossip on national TV with the likes of Tim Russert and Don Imus-gives us more motivation to follow her psychological musings.

Wait Till Next Year is a memoir of the author's childhood between the ages of five and twelve, roughly 1949 through 1956. Doris Kearns was the last of three daughters of Michael and Helen Kearns. Michael Kearns commuted to New York on the Long Island Railroad and made very decent money as a middle level bank officer; he owned a home in Rockville Center, and poverty was never a factor in the author's upbringing. Doris Kearns did well in school, had lots of friends, and objectively speaking, enjoyed the benefits of robust American prosperity.

All the same, her childhood was marked with sadness, fear, and trauma. Some of these features were cultural: the author recalls recoiling from a televised picture of Joe McCarthy, crouching on the floor during an atomic bomb drill, and avoiding public places for fear of polio. But her major crosses were within the family, and specifically involving her mother. Helen Kearns, we learn gradually, is wasting away. In many understated ways the author chronicles her decline-her mother's need for silence and naps, her pallor and angina attacks, her inability to do strenuous things that other mothers did with and for their daughters. Young Doris Kearns confesses to a very natural ambivalence-worry about her mother's life coupled with resentment over her mother's limitations.

Those who do not follow baseball do not have an appreciation for the psychological grounding it provides its followers in times of stress. Doris was introduced to radio broadcasts of timeless baseball by the time she was five, and soon after she mastered the art of official scoring in a red score book purchased for her by her father, who kindly shielded from his daughter the fact that all of New York's many newspapers carried the box scores for public consumption. Doris thus enjoyed the satisfaction of replaying each afternoon's games for her father as he sipped his evening cocktail. She attributes this experience with implanting the basic skills of research and story telling, the prerequisites for an up-and-coming historian of note. The author's substantive emotional involvement with "Dem Bums," the Brooklyn Dodgers, was in fact the tonic that helped her weather the cultural and familial storms of her youth. And the bonds established between father and daughter through the medium of baseball helped her to forgive him in her later teen years when her father's grief led him into a period of gross insensitivity to his daughter's needs.

I found myself more than a little envious when I learned in the epilogue that the author, by now the famous Dr. Kearns-Goodwin, literally reconstructed her old neighborhood in middle age through a meticulous search of records for her old Rockville Center chums, whose interviews enrich the telling of this very personal tale. I understand her motivation as I progress through middle age. We are always in dialogue with the child within us, or at least the child we think were. What hinders us most often is a lack of information, and what we desire is a pilgrimage backward to legitimate past experience. This work at hand is Doris Kearns Goodwin's journey into her past. It was certainly not a painless adventure. But in turning the final page, the reader is pleased that at least one child-adult was able to cross to the other side and go home again.

(From quoting Thomas Burns, USA)

Target readers:

People who miss the happy and simple days of the 1950s, who love baseball and who appreciate the hauntingly beaufiful writing of the author.

|

|

- Better with -

Better with

The Measure of a Man: A Spiritual Autobiography (Oprah's Book Club) (Paperback)

:

|

|

Doris Kearns Goodwin won the Pulitzer Prize in history for No Ordinary Time, which was a New York Times bestseller. She is also the author of bestsellers The Fitzgeralds and the Kennedys and Lyndon Johnson and the American Dream. She is a political analyst for The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer and lives in Concord, Massachusetts, with her husband, Richard Goodwin, and their three sons.

****

In Author's Own Words:

I trace my love of history to the days when I was six years old and my father taught me the mysterious art of keeping score at baseball games so that I could listen to the Dodgers play in the afternoons while he was at work and re-create for him at night the entire history of each day's game, play by play, inning by inning. He made it even more special for me because he never told me that all this was described in the newspapers the next day so that I thought without me he would never even know what happened to our beloved Dodgers! Thus history acquired for me a magic that it still holds to this day.

But if my love of history was planted in that childhood experience, my

particular style of writing - a love of storytelling and an attempt to fuse history and biography with as much detail as possible so that the characters can come alive for the reader-is rooted in the experience of knowing one president Lyndon Johnson - very well when I was only thirty four. I worked for him first as a White House Fellow in his last year in office and then helped him on his memoirs the last four years of his life. It should have been a time in his life when he had much to be grateful for. His career in politics had, after all, reached a peak with his election to the presidency and he had all the money he needed to pursue any leisure activity. But here was a man whose entire life had been consumed by power, success, and ambition, and as a result, he could barely get through the days once the presidency was gone.

And, in his vulnerable state, he opened up to me in ways he never would have, had I known him at the height of his power, telling me of his fears, his nightmares, and his sorrows.

It was this experience that fired within me the drive to understand the inner person behind the public image that I'd like to believe I have brought to each of my books, beginning with Lyndon Johnson and the American Dream, published in 1976 when I was still teaching at Harvard where I had gotten my Ph.D. in 1968. Watching Johnson's desolation at the end of his life also had an impact on my personal life. I had started my second book, The Fitzgeralds and the Kennedys, shortly after I was married and had two sons in two years. I was still a professor at Harvard, trying to teach, write, and be a mother at the same time and doing nothing right. The image of Johnson's sad retirement helped me to make some choices-to give up teaching so that I could stay at home with my children and write. Even then, it took ten years to write the Kennedy book, which was finally published in 1987. But when I look at the young men my boys have become, I have never regretted the years I spent at home.

I was drawn to my third book, No Ordinary Time, by a fascination both with the period of time, a time when our country was united by a common cause against a common enemy, and by a fascination with the extraordinary partnership between Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt. The research was a labor of love: I spent months at a time at Hyde Park, New York, conducted hundreds of interviews with people who knew the Roosevelts personally, perused dozens of diaries and thousands of letters, read old newspapers and magazines, and truly felt as if I had been transported back 50 years in time.

|

|

From Publisher

Set in the suburbs of New York in the 1950s, Wait Till Next Year is Doris Kearns Goodwin's touching memoir of growing up in love with her family and baseball. She re-creates the postwar era, when the corner store was a place to share stories and neighborhoods were equally divided between Dodger, Giant, and Yankee fans.

We meet the people who most influenced Goodwin's early life: her mother, who taught her the joy of books but whose debilitating illness left her housebound: and her father, who taught her the joy of baseball and to root for the Dodgers of Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, Pee Wee Reese, Duke Snider, and Gil Hodges. Most important, Goodwin describes with eloquence how the Dodgers' leaving Brooklyn in 1957, and the death of her mother soon after, marked both the end of an era and, for her, the end of childhood.

|

From Chapter One

When I was six, my father gave me a bright red scorebook that opened my heart to the game of baseball. After dinner on long summer nights, he would sit beside me in our small enclosed porch to hear my account of that day's Brooklyn Dodger game. Night after night he taught me the odd collection of symbols, numbers, and letters that enable a baseball lover to record every action of the game. Our score sheets had blank boxes in which we could draw our own slanted lines in the form of a diamond as we followed players around the bases. Wherever the baserunner's progress stopped, the line stopped. He instructed me to fill in the unused boxes at the end of each inning with an elaborate checkerboard design which made it absolutely clear who had been the last to bat and who would lead off the next inning. By the time I had mastered the art of scorekeeping, a lasting bond had been forged among my father, baseball, and me.

All through the summer of 1949, my first summer as a fan, I spent my afternoons sitting cross-legged before the squat Philco radio which stood as a permanent fixture on our porch in Rockville Centre, on the South Shore of Long Island, New York. With my scorebook spread before me, I attended Dodger games through the courtly voice of Dodger announcer Red Barber. As he announced the lineup, I carefully printed each player's name in a column on the left side of my sheet. Then, using the standard system my father had taught me, which assigned a number to each position in the field, starting with a "1" for the pitcher and ending with a "9" for the right fielder, I recorded every play. I found it difficult at times to sit still. As the Dodgers came to bat, I would walk around the room, talking to the players as if they were standing in front of me. At critical junctures, I tried to make a bargain, whispering and cajoling while Pee Wee Reese or Duke Snider stepped into the batter's box. "Please, please, get a hit. If you get a hit now, I'll make my bed every day for a week." Sometimes, when the score was close and the opposing team at bat with men on base, I was too agitated to listen. Asking my mother to keep notes, I left the house for a walk around the block, hoping that when I returned the enemy threat would be over, and once again we'd be up at bat. Mostly, however, I stayed at my post, diligently recording each inning so that, when my father returned from his job as bank examiner for the State of New York, I could re-create for him the game he had missed.

When my father came home from the city, he would change from his three-piece suit into long pants and a short-sleeved sport shirt, and come downstairs for the ritual Manhattan cocktail with my mother. Then my parents would summon me for dinner from my play on the street outside our house. All through dinner I had to restrain

myself from telling him about the day's game, waiting for the special time to come when we would sit together on the couch, my scorebook on my lap.

"Well, did anything interesting happen today?" he would begin. And even before the daily question was completed I had eagerly launched into my narrative of every play, and almost every pitch, of that afternoon's contest. It never crossed my mind to wonder if, at the close of a day's work, he might find my lengthy account the least bit tedious. For there was mastery as well as pleasure in our nightly ritual. Through my knowledge, I commanded my father's undivided attention, the sign of his love. It would instill in me an early awareness of the power of narrative, which would introduce a lifetime of storytelling, fueled by the naive confidence that others would find me as entertaining as my father did.

Michael Francis Aloysius Kearns, my father, was a short man who appeared much larger on account of his erect bearing, broad chest, and thick neck. He had a ruddy Irish complexion, and his green eyes flashed with humor and vitality. When he smiled his entire face was transformed, radiating enthusiasm and friendliness. He called me "Bubbles," a pet name he had chosen, he told me, because I seemed to enjoy so many things. Anxious to confirm his description, I refused to let my enthusiasm wane, even when I grew tired or grumpy. Thus excitement about things became a habit, a part of my personality, and the expectation that I should enjoy new experiences often engendered the enjoyment itself.

These nightly recountings of the Dodgers' progress provided my first lessons in the narrative art. From the scorebook, with its tight squares of neatly arranged symbols, I could unfold the tale of an entire game and tell a story that seemed to last almost as long as the game itself. At first, I was unable to resist the temptation to skip ahead to an important play in later innings. At times, I grew so excited about a Dodger victory that I blurted out the final score before I had hardly begun. But as I became more experienced in my storytelling, I learned to build a dramatic story with a beginning, middle, and end. Slowly, I learned that if I could recount the game, one batter at a time, inning by inning, without divulging the outcome, I could keep the suspense and my father's interest alive until the very last pitch. Sometimes I pretended that I was the great Red Barber himself, allowing my voice to swell when reporting a home run, quieting to a whisper when the action grew tense, injecting tidbits about the players into my reports. At critical moments, I would jump from the couch to illustrate a ball that turned foul at the last moment or a dropped fly that was scored as an error.

"How many hits did Roy Campanella get?" my dad would ask. Tracing my finger across the horizontal line that represented Campanella's at bats that day, I would count. "One, two, three. Three hits, a single, a double, and another single." "How many strikeouts for Don Newcombe?" It was easy. I would count the Ks. "One, two... eight. He had eight strikeouts." Then he'd ask me more subtle questions about different plays - whether a strikeout was called or swinging, whether the double play was around the horn, whether the single that won the game was hit to left or right. If I had scored carefully, using the elaborate system he had taught me, I would know the answers. My father pointed to the second inning, where Jackie Robinson had hit a single and then stolen second. There was excitement in his voice. "See, it's all here. While Robinson was dancing off second, he rattled the pitcher so badly that the next two guys walked to load the bases. That's the impact Robinson makes, game after game. Isn't he something?" His smile at such moments inspired me to take my responsibility seriously.

Sometimes, a particular play would trigger in my father a memory of a similar situation in a game when he was young, and he would tell me stories about the Dodgers when he was a boy growing up in Brooklyn. His vivid tales featured strange heroes such as Casey Stengel, Zack Wheat, and Jimmy Johnston. Though it was hard at first to imagine that the Casey Stengel I knew, the manager of the Yankees, with his colorful language and hilarious antics, was the same man as the Dodger outfielder who hit an inside-the-park home run at the first game ever played at Ebbets Field, my father so skillfully stitched together the past and the present that I felt as if I were living in different time zones. If I closed my eyes, I imagined I was at Ebbets Field in the 1920s for that celebrated game when Dodger right fielder Babe Herman hit a double with the bases loaded, and through a series of mishaps on the base paths, three Dodgers ended up at third base at the same time. And I was sitting by my father's side, five years before I was born, when the lights were turned on for the first time at Ebbets Field, the crowd gasping and then cheering as the summer night was transformed into startling day.

|

|

| View all 11 comments |

Ann Hulbert (The New York Times Book Review) (MSL quote), USA

<2007-01-18 00:00>

In a season awash in X-rated memoirs, Wait Till Next Year is an anomaly: a reminiscence that is suitable, in fact ideal, for a preadolescent readership of not just girls but boys too. Move over, Judy Blume, Matt Christopher and the American Girl doll books. For self-esteem-building female role models, for baseball lore and inning-by-inning action and for a lively trip into the recent American past, you could hardly do better. |

Jodi Daynard (The Boston Globe), USA

<2007-01-18 00:00>

Lively, tender, and... hilarious... [Goodwin's] memoir is uplifting evidence that the American dream still exists - not so much in the content of the dream as in the tireless, daunting dreaming.

|

Peter Delacorte (San Francisco Chronicle Book Review) (MSL quote), USA

<2007-01-18 00:00>

A poignant memoir... marvelous... Goodwin shifts gracefully between a child's recollection and a adult's overview.

|

Maggie Gallagher (The Baltimore Sun) (MSL quote), USA

<2007-01-18 00:00>

As the tenured radicals attempt to rewrite our nation's history, the warm, witty, eloquent personal testimony of someone of Doris Kearns Goodwin's stature is well worth reading. |

View all 11 comments |

|

|

|

|