|

|

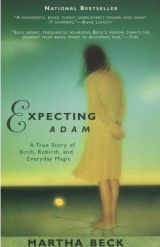

Expecting Adam: A True Story of Birth, Rebirth, and Everyday Magic (Paperback)

by Martha Beck

| Category:

Teens, Autobiography, Inspirational |

| Market price: ¥ 158.00

MSL price:

¥ 148.00

[ Shop incentives ]

|

| Stock:

Pre-order item, lead time 3-7 weeks upon payment [ COD term does not apply to pre-order items ] |

MSL rating:

Good for Gifts Good for Gifts |

| MSL Pointer Review:

Wickedly funny and wrenchingly sad memoirs of a young mother awaiting the birth of a Down syndrome baby while simultaneously pursuing a doctorate at Harvard. |

| If you want us to help you with the right titles you're looking for, or to make reading recommendations based on your needs, please contact our consultants. |

Detail |

Author |

Description |

Excerpt |

Reviews |

|

|

|

Author: Martha Beck

Publisher: Berkley Trade; Reissue edition

Pub. in: August, 2000

ISBN: 0425174484

Pages: 336

Measurements: 8.3 x 5.3 x 0.9 inches

Origin of product: USA

Order code: BC00345

Other information: ISBN-13: 978-0425174487

|

|

Rate this product:

|

|

- Awards & Credential -

A national and New York Times best-seller. |

|

- MSL Picks -

"He says you'll never be hurt as much by being open as you have been by remaining closed."

The messenger is a school janitor with a master's in art history who claims to be channeling "from both sides of the veil." "He" is Adam, a three-year-old who has never spoken an intelligible word. And the message is intended for Martha Beck, Adam's mother, who doesn't know whether to make a mad dash for the door to escape a raving lunatic (after all, how many conversations like this one can you have before you stop getting dinner party invitations and start pushing a mop yourself?) or accept another in a series of life lessons from an impeccable but mysterious source.

From the moment Martha and her husband, John, accidentally conceived their second child, all hell broke loose. They were a couple obsessed with success. After years of matching IQs and test scores with less driven peers, they had two Harvard degrees apiece and were gunning for more. They'd plotted out a future in the most vaunted ivory tower of academe. But the dream had begun to disintegrate. Then, when their unborn son, Adam, was diagnosed with Down syndrome, doctors, advisers, and friends in the Harvard community warned them that if they decided to keep the baby, they would lose all hope of achieving their carefully crafted goals. Fortunately, that's exactly what happened.

Expecting Adam is a poignant, challenging, and achingly funny chronicle of the extraordinary nine months of Martha's pregnancy. By the time Adam was born, Martha and John were propelled into a world in which they were forced to redefine everything of value to them, put all their faith in miracles, and trust that they could fly without a net. And it worked.

Martha's riveting, beautifully written memoir captures the abject terror and exhilarating freedom of facing impending parentdom, being forced to question one's deepest beliefs, and rewriting life's rules. It is an unforgettable celebration of the everyday magic that connects human souls to each other.

(Quoting from The Publisher)

Target readers:

Young adults, couples, women.

|

|

Martha Beck, the "Quality of Life" columnist for Mademoiselle, is a career counselor and the author of Breaking Point: Why Women Fall Apart and How They Can Re-Create Their Lives. She also hosts a weekly TV spot, "Ask Martha," on Good Day Arizona.

|

|

From The Publisher

The "slyly ironic, frequently hilarious" (Time) memoir about angels, academics, and a boy named Adam...

A national bestseller and an important reminder that life is what happens when you're making other plans.

Put aside your expectations. This "rueful, riveting, piercingly funny" (Julia Cameron) book is written by a Harvard graduate - but it tells a story in which hearts trump brains every time. It's a tale about mothering a Down syndrome child that opts for sass over sap, and it's a book of heavenly visions and inexplicable phenomena that's as down-to-earth as anyone could ask for. This small masterpiece is Martha Beck's own story - of leaving behind the life of a stressed-out superachiever, opening herself to things she'd never dared consider, meeting her son for (maybe) the first time... and "unlearn[ing] virtually everything Harvard taught [her] about what is precious and what is garbage."

"Beck [is] very funny, particularly about the most serious possible subjects--childbirth, angels and surviving at Harvard." - New York Times Book Review

"Immensely appealing... hooked me on the first page and propelled me right through visions and out-of-body experiences I would normally scoff at." - Detroit Free Press

"I challenge any reader not to be moved by it." - Newsday

"Brilliant." - Minneapolis Star-Tribune

|

This happened when Adam was about three years old.

I was sitting in a small apartment with a woman I had barely met, talking to her about her life. I'll call her Mrs. Ross, because it isn't her name. I had been doing similar interviews for months, collecting data for my Ph.D. dissertation. Mrs. Ross was a scrawny forty-five-year-old with a master's degree in art history and a job as an elementary school janitor. I was taking notes, considering what this woman's experience had to teach about the real-world value of the more refined academic fields, when she suddenly stopped talking.

There was a moment of silence, and then I looked up and said, "Yes?" in a helpful voice, which was normally enough to keep an interview rolling. But Mrs. Ross wasn't acting normal. She had been sitting on a straight-backed wooden chair, both feet set firmly on the floor and her hands resting primly on her knees. Now she was curled into an almost fetal position, forearms crushed between the tops of her thighs and her chest, her eyes tightly closed.

I became alarmed. "Are you all right?" I said, trying to sound politely but not overly curious.

Mrs. Ross waved a hand at me. "I can't . . . quite . . . make it out," she said.

I just stared at her.

"Usually," she gasped, her eyelids clamping down tighter, "usually I can tell which side of the veil it's coming from . . . that's usually the first thing I can tell . . . but this time I . . . can't."

"Uh-huh," I said cautiously, glancing toward the door, wondering if I could get to it before Mrs. Ross leapt upon me like a mad dog.

"It's like . . . he's not really on one side of the veil or the other . . . maybe he's on both." She shook her head, troubled. "At least I know it's a he."

"Uh, Mrs. Ross," I said, gathering my notes together for a quick exit.

At this point Mrs. Ross's eyes flew open wide, fixing me with a bloodshot stare.

"You know who it is!" she said in a low, accusing voice. "You know who it is, but you're blocking!"

At this point my curiosity began to get the better of me. "I know who?" I said.

"That's right!" Mrs. Ross uncurled a little. "You see, I have this . . . well, it's a gift." She sounded as though she wasn't quite sure Santa had gotten her letters.

"Gift?" I repeated.

She nodded. "I get messages for people." She sighed and sat up. "There was a point in my life when I stopped talking about it, you know, because it's very embarrassing."

"Oh," I said.

"And then, you know," Mrs. Ross continued, "I began to lose it. It was getting fainter, and sometimes the spirits would be angry at me, because I wouldn't help them get through to people."

At this moment, I swear to God, a large green parrot walked out of Mrs. Ross's small kitchen and into the living room. It paced slowly across the carpet, peered at me suspiciously with one flinty eye, then proceeded on foot up the leg of Mrs. Ross's chair and onto her shoulder. She's a witch, I thought. I'm sitting here talking to a genuine witch. The parrot was obviously a familiar. I would have been willing to bet it was her husband.

Mrs. Ross kept talking, stroking the bird absentmindedly. "So I promised God that I would always deliver the messages as soon as I got them. No matter what."

"No kidding." I said this without any sarcasm. That's how much I had changed. Four years earlier I would have dismissed Mrs. Ross and her "gift" immediately. Back then I had known exactly how the world worked. Back then I had been sure of my own intellect, sure of the primacy of Reason, sure that, given enough time and training, I could control my destiny. That was before Adam. But now it was four years later, and Adam was at home with the baby-sitter, and I had learned a lot about how much I had to learn. So I sat still and waited for Mrs. Ross to go on. She did.

"The messages are usually from the other side of the veil--I mean, from the spirit world," she said. "Sometimes they're from living people who are far away and need to get a message through immediately. But that's always the first thing I can tell--which side of the veil the message is coming from." Her brow furrowed. "And this time, I can't tell."

By now, I admit it, I was hooked. I wanted my message.

"Just relax," I suggested helpfully.

Mrs. Ross shot me a glance that would have pierced steel, a glance designed to shove me off her turf.

"Or not," I said.

"We should pray," whispered Mrs. Ross.

"Uh, okeydokey," I responded. I mean, what would you have done?

So Mrs. Ross and I bowed our heads, and I drew a deep breath and relaxed for just a second, and then her head snapped up like a Pez dispenser and she said, "All right, you stopped blocking. It's your son."

"My son?" Even after everything that had already happened, this surprised me. I had been hoping the message would be from my guardian angel, or perhaps a stray ancestor with an interest in my career.

"You have a son who's halfway between worlds," stated Mrs. Ross.

I felt the hair go up on my arms. You see, no matter how much evidence you have, over time you tend to block out the experiences that aren't "normal." Who wants to turn into a Mrs. Ross, blurting out gibberish about spirits and veils? How much of that sort of conversation are you allowed before people stop inviting you to parties, and you end up pushing a mop in an elementary school?

"Well," I said to Mrs. Ross, "maybe I do have a son . . . uh . . . like that."

She gave me a withering look. "You do," she said flatly. "And he wants me to give you a message." The parrot nibbled tenderly on her ear.

By now my whole body was bristling with a strange electricity. The sensation had become familiar to me over the past few years, yet it was always a surprise. At least I kept my mouth shut.

Mrs. Ross closed her eyes again, gently this time. "He says that he's been watching you very closely from both sides of the veil."

The veil again.

"He says that you shouldn't be so worried. He says you'll never be hurt as much by being open as you have been hurt by remaining closed."

She opened her eyes, scratched the parrot's head, and smiled. She didn't look like a witch at all anymore.

"That's it?" I said.

Mrs. Ross nodded, smiling.

I didn't return the smile. "What the heck is that supposed to mean?"

She shrugged. "Beats me."

"Oh, come on," I pleaded. "There's got to be more. Ask him." This is not the way I was taught to behave at Harvard.

"I don't ask questions," she said. "I just deliver messages. Like Western Union. What the messages mean is none of my business."

And that was all she had to say.

After a pathetic attempt to pretend I was still conducting an interview, I raced home to confront Adam. He was in his crib, asleep. He was about half the size of a normal three-year-old, had barely learned to walk, and had never spoken an intelligible word. I reached down and poked him in the tummy, and he woke up with his usual jolly grin on his face.

I looked into his small, slanted eyes. "Adam," I said seriously. "You've got to tell me. Are you sending me messages through Mrs. Ross?"

His smile broadened. That was all. And he hasn't said a thing about it since.

So here I am, still wondering what the hell happened that day, wondering whether Mrs. Ross was really channeling my three-year-old, wondering what he meant. I wonder a lot of things, since Adam came along. I wonder about all the strange and beautiful and terrible things that accompanied him into my life. My husband, John, knows about my wondering--shares it, in fact, since his life, too, was changed when we were expecting Adam. But when I wasn't talking to John, I learned to keep it all to myself. I learned to ignore the miraculous in my life, to pretend it didn't exist, to tell lies in order to be believed. In short, I kept myself closed.

This has not been easy. It is difficult not to tell people when one of your interview subjects turns out to be Parrot Woman. The strangeness, the curiosity, the wonder keeps pushing outward, begging to be communicated, needing air and company. On many occasions, I have tried to talk about Adam without letting on that I actually believed in everything that happened to me. I have written this book twice already, both times as a novel, to wit: "This is the story of two driven Harvard academics who found out in midpregnancy that their unborn son would be retarded. To their own surprise and the horrified dismay of the university community, the couple ignored the abundant means, motive, and opportunity to obtain a therapeutic abortion. They decided to allow their baby to be born. What they did not realize is that they themselves were the ones who would be 'born,' infants in a new world where magic is commonplace, Harvard professors are the slow learners, and retarded babies are the master teachers."

You see, by calling it a novel, I could tell the story without putting myself in danger from skeptics, scientists, and intellectuals. "Fiction!" I would assure them. "Made it all up! Not a word of truth in it!" Then they would all go away and leave me alone, and perhaps a few sturdy souls would be willing to believe me, and I could open up in safety to them.

It hasn't worked out that way. The editors and agents and writers I respect most have always come back, after reading my "novel," with the same question: "Excuse me, but how much of this is fiction?" And I would hem and haw a bit before admitting that aside from making John and myself sound much better-looking than we are, I didn't fictionalize anything. It's all true, I would say. Then I would sink into my chair five or six inches and wait for them to call security.

So far, that hasn't happened. It has been five years since Mrs. Ross reared back against her parrot and delivered Adam's message, and in all that time my favorite people have continually repeated his advice. Open up, they say. It will feel better than remaining closed.

I am none too sure about this. I am very much afraid of being caught in the firestorms of controversy over abortion, genetic engineering, medical ethics. It worries me to think that I will be lumped together with the right-to-lifers, not to mention every New Age crystal kisser who ever claimed to see an angel in the clouds over Sedona. I am reluctant to wave good-bye to my rationalist credibility. Nevertheless, the story will not stop unfolding, and it will not stop asking me to tell it. I have resisted it for what feels like a very long time, hoping it would back off and disappear. But it hasn't.

So, Mrs. Ross, wherever you are, thank you for delivering my son's message. After all these years, I've finally decided to listen. |

|

| View all 12 comments |

Julia Flyte (MSL quote), USA

<2007-02-27 00:00>

I am pregnant, and I was curious to read this book to get a better idea of what it might be like to have a child with Down's Syndrome. Although I enjoyed reading "Expecting Adam", it wasn't at all what I was expecting.

Martha Beck's story is intensely personal. She talks about how her life and her husband's life were transformed by the experience of her carrying and giving birth to Adam, a baby with Down's Syndrome. Throughout her pregnancy they both experienced a number of spiritual experiences and miracles. Subsequent to his birth, Adam has brought much joy and wonder into their lives, completely rearranging their priorities and attitudes to life.

However Martha makes it clear that she doesn't view this as being because Adam has Down's Syndrome. At one stage she consults a psychic who refers to Adam as being an "angel", but who also stresses that his disability is merely a coincidence rather than a factor contributing to his angelic status. Martha makes it clear that she doesn't necessarily view all children with Down's as being as special as Adam. This presents an interesting question about what makes Adam so special and about whether the fact that he has Down's is even relevant to Martha's story.

So rather than being a book about what it is like to carry and give birth to a baby with Down's Syndrome, this book is about what it is like to be transformed from being an ambitious and driven academic to a more spiritual person, by the experience of carrying a child who appears to have spiritual powers. At times I felt that I was reading a memoir written by Mary about being pregnant with the baby Jesus.

Because Martha writes well and her story is told with some humor, I enjoyed reading the book. However I got increasingly frustrated as I went on by how extraordinary she felt her experience to be, and how little I could take from it that was relevant to me or anyone that I knew.

|

Liane (MSL quote), USA

<2007-02-27 00:00>

Maya Angelou once said that "there is no greater agony than holding an untold story inside of you." This piece of work represents Martha Beck's luminous journey towards choosing to mother Adam, her son who was prenatally diagnosed with Down's Syndrome.

Like many mothers of exceptional children I've known, Martha has touched on the one theme most of us feel reluctant to talk about - that our lives are peppered with unexplainable, prescient experiences that served to pave our way towards accepting a child that a highly educated world often believes is less than worthy of a chance at life.

Because Ms. Beck's Harvard Education and academic's resume brings the reader into a metaphycial journey towards coming to accept Adam through a skeptics eyes, her story seems more credible than that of the average person who sits down to write a book that says "oh, but my child is so much more than what he seems."

Martha's tale is as convincing as it is spellbinding. Her range as a writer is vast - she is both a comedian and an accomplished dramatist.

Expecting Adam hits its intended mark. It reminds us that every child comes into this world for reasons that often lay beyond the realm of human reckoning. It offers proof that all lives have purpose, meaning and dignity. On top of all this, Expecting Adam offers the reader the benefit of an excellent writer.

As the mother of two boys with autism, one who "came back" and one who "didn't", I commend this writer for sharing her story.

Ms. Beck's experiences felt universal to me, and true in a way I can't begin to put into words.

When I look into my children's eyes, I understand without reservation that nothing is left to chance. Like Ms. Beck, I feel both humbled and awed by the opportunity to mother children like mine.

It is impossible to read "Expecting Adam", and fail to see that every life has meaning and dignity.

For all things, there is a season...

|

Nancy McNamara (MSL quote), USA

<2007-02-27 00:00>

Expecting Adam is not the story of a child with Down syndrome. It is the heart-felt confession of one woman's personal journey from fear to grace. As the mother of an eight year old boy with an autistic disorder, I fought and wrangled with her story for about the first half of the book, and found myself saying "Come on, Martha, tell me something I don't know." Having conceived my second child while my husband was completing his doctorate, I found eerie similarities to my own experience, from questioning mysticism and other - worldly phenonoma, to being in complete awe of our son when he does what we call his "God Thing." Even so I felt she was exaggerating her own experience,and taking liberties with the academic environment in which she lived. Since most readers won't have an insider's understanding of what it is like be the parents of a "non-perfect" baby in the halls of academia, I felt that I would qualify any recommendation that I made by saying, "Take in all the parts except Harvard - she went a bit overboard there."

But then, somewhere in the middle of the book, it was as if Martha was right there whispering in my ear, "open your heart..." And so, I did. The next morning, after finishing the book, I was shouting orders to my four children, doing my best Captain von Trapp imitation, and getting nowhere fast in readying them for school. There was spilled juice, slopped cereal, and a screaming baby. My "disabled" son, sensing my mounting frustration, asked just at the wrong moment to have his shoes tied. I threw down the kitchen towel in exasperation and left the room for a few minutes to collect myself. I then sheepishly returned to the rallying cry of, "Lets all be chickens!" And there he was, my son, making the others laugh and smile, clearing away the mess, collecting backpacks, and all the while flapping his arms like wings and making his best chicken sounds. We all piled into the car, slightly late, but smiling, and as he got out he gave me a wet, sloppy kiss. He took me by the shoulders and said, "Mommy, if I ever lose you, my heart will not feel so good." He walked away, doing his best imitation of a man walk, and I drove back home, crying and laughing at the same time.

And then I felt them. Martha's Bunraku puppeteers. Or at least, my own version of them. Because at that moment I have never been happier to be parent, let alone the parent of a child with very special needs. All my fears for his future (and mine) were obliterated by a wonderfully calm place in my heart, something I have felt many times before, but could never have expressed as beautifully and honestly as Martha Beck. Thank you, Martha, for putting into words so many of the feelings that I have, but have been too fearful to admit and put down on paper. I hope that I become more graceful in time with my own journey, as you have shown the world that you are with yours.

|

John Foraker (MSL quote) , USA

<2007-02-27 00:00>

As a mother of an eight month old baby with Down Syndrome, I avoided this book at first because I thought it would be too wrenching and close to home. It had the opposite effect. It has been an absolutely incredible experience. Martha Beck bravely and genuinely shares her true account of her pregnancy and experiences before and after her son Adam's birth. She discovers he has Down Syndrome before he is born but cannot even consider abortion. Throughout the nine months, Martha (and her husband)experience many paranormal/spiritual events. This might seem unconvincing or even wacky from any other source, but as a Harvard trained academician, Martha makes her story not only plausible but grippingly real. Her sense of humor is hilarious and I openly laughed out loud several times! I also openly wept at her raw and vivid descriptions of the revulsion so many of us have for those who are different. I think this book is a fantastic tool for parents of children with disabilities to give to the outside world. This is how we see our children, truly! It would also be a terrific book for any teacher or educator to read. To me, it's been a hope, a salve, an inspiration.

|

View all 12 comments |

|

|

|

|