|

|

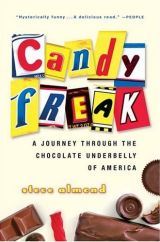

Candyfreak: A Journey through the Chocolate Underbelly of America (Paperback)

by Steve Almond

| Category:

Entrepreneurship, Innovation, Business success, Corporate history |

| Market price: ¥ 148.00

MSL price:

¥ 128.00

[ Shop incentives ]

|

| Stock:

Pre-order item, lead time 3-7 weeks upon payment [ COD term does not apply to pre-order items ] |

|

|

MSL rating:

Good for Gifts Good for Gifts |

| If you want us to help you with the right titles you're looking for, or to make reading recommendations based on your needs, please contact our consultants. |

Detail |

Author |

Description |

Excerpt |

Reviews |

|

|

|

Author: Steve Almond

Publisher: Harvest Books

Pub. in: April, 2005

ISBN: 0156032937

Pages: 288

Measurements: 7.8 x 5.4 x 1 inches

Origin of product: USA

Order code: BA01173

Other information: ISBN-13: 978-0156032933

|

|

Rate this product:

|

|

- MSL Picks -

I figured I would be very interested. Like Steve Almond does in the first pages of his book Candyfreak, I must disclose my current candy count: there is roughly a pound of Ghirardelli Dark squares in my desk drawer, a half-dozen Galak white chocolate squares on my desk, two Kit-Kats, some Starbuck's After Coffee Gum someone gave me, and a half pound of local chocolatier Gardener's chocolate covered pretzels in my fridge. I have very little on hand compared to what Almond says he has regularly, but I still know a kindred spirit when I see one. So, by the time I hit page 4 of Candyfreak, I knew I would love it, just reading Almond's ability to synthesize the experience of a candy bar: " ... the whipped splendor of the Choco-Lite, whose tiny air pockets provided such a piquant crunch (the oral analogue to stomping on bubble wrap)." The book never lets up from there, reveling in candy, particularly chocolate, in Almond's signature sentences which move like referential dervishes.

In Candyfreak, Almond parlays his own obsession with chocolate into a quest to seek out the sources and practices of today's chocolate confection, as well as to learn about the forces that have overwhelmed the artistry and pluck of individual chocalatiers into the mechanized behemoth of American mass culture. Throughout, Almond tempers his political urgencies with his own disarming awe and glee at the industry and its products, and he also deals with unfolding family tragedies. His grandfather is dying, while at the same time Almond realizes his lifelong zeal for chocolate both saved his life and "broke his spirit." If it sounds like too much to cram in, perhaps you've not read Almond's ambitious book of sort stories, My Life in Heavy Metal, a book that will give you faith in Almond's ability to multi-task, regardless of genre.

Almond's prose packs a sensory wallop at all times. It is also candid, direct, and muscular- he wastes no space. Because of his economy, his writing is akin to the best candy: all good stuff, no fill or the useless air that puffs up the wretched Three Musketeers bar. When he rattles off the names of regional candybars now gone to mass marketers, he says their names are "incantatory poetry." When he says he doesn't like coconut, he says it's like "chewing on a sweetened cuticle." The writing says it: candy, chocolate in particular, for Almond is a passion, a "freak." And like all freaks, Almond has his rage, and the loss of a particular candybar, the Caravelle, and his subsequent despondency and rampage after any sign of it led him to consider the book.

Almond meditates on the sources of his "freak," including its lineage. His father's passion for Junior Mints he sees as a thing to awe: "I loved watching him eat these, patiently, with moist clicks of the tongue. I loved his mouth, the full, pillowy lips, the rakishly crooked teeth-the mouth of a closet sensualist." After some consideration of the roots, however, he's off, interviewing confectioners, visiting factories and tasting candy fresh out of the "enrober" (a device to which he devotes many fine lines), squirreling away samples, and trying to see what did happen to chocolate in America. The short answer is, well, the same thing that happened virtually to every worthwhile thing from beer to sports: mass distribution, mass advertising, mass culture, mass dumbing down.

The short answer doesn't do justice to Almond's work because Candyfreak does what the best creative nonfiction does: reports something in unerring detail, educates about a topic we thought we knew a thing or two about, tells a story both about the author and about the subject, and delivers the whole package in style. Almond's fevered style-known to many from his short stories-here finds a subject about which many folks feel feverish, and the result is one of the most entertaining books I've read in a while.

Almond's tries to balance political fantasy and the reality of the urge: "In my own pathologically romantic sense of things, I viewed [little] companies as throwbacks to a bygone era of candy, when each town had its individual brands. And the good peoples of this country would gather together, in public squares with lots of trees and perhaps a fellow picking a banjo, and they would partake of the particular candy bar produced in their town and feel a surge of sucrose-fueled civic identity. What I really wanted to do was visit these companies-if nay still existed-and to chronicle their struggles for survival in this wicked age of homogeneity, and, not incidentally, to load up on free candy."

While he showcases opinions and can seem hostile at times in his discernment, he is not faddish or uncritical: "The new chocolate specialty products are equally pretentious. I ask you, does the world truly need a bar infused with hot masala? The latest rage, as of this writing, is super-concentrated chocolate, with a cocoa content in the 90 percent range, a trend that will, in due time, allow us to eat Baker's Chocolate at ten bucks a square."

Opinionated, deftly and surprisingly written, thoroughly experienced, and surprisingly moving, Steve Almond's Candyfreak will have you wandering into specialty stores hoping they have candy racks. It will have you looking down your nose at M&Ms, for perhaps the first time in your life. It will have you cruising the Internet for the Five Star Bar, hoping the taste lives up to the writing. It will have you thinking about chocolate for weeks afterward, more than you ever have. And it will have you wanting to return to the book, again and again, to find those sentences, those toothsome, goo-on-your-chin, crunchulicious miracles of sentences, and to wish everyone you know the pleasure of experiencing the world, for a little while anyway, mouth first.

(From quoting Gabriel Welsch, USA)

|

|

Steve Almond is the author of the acclaimed story collection My Life in Heavy Metal. He is a regular commetator on the NPR affiliate WBUR in Boston, teaches creative writing at Boston College, and has eaten at least one piece of candy every single day of his entire life.

|

|

From Publisher

A self-professed candyfreak, Steve Almond set out in search of a much-loved candy from his childhood and found himself on a tour of the small candy companies that are persevering in a marketplace where big corporations dominate.

From the Twin Bing to the Idaho Spud, the Valomilk to the Abba-Zaba, and discontinued bars such as the Caravelle, Marathon, and Choco-Lite, Almond uncovers a trove of singular candy bars made by unsung heroes working in old-fashioned factories to produce something they love. And in true candyfreak fashion, Almond lusciously describes the rich tastes that he has loved since childhood and continues to crave today. Steve Almond has written a comic but ultimately bittersweet story of how he grew up on candy-and how, for better and worse, the candy industry has grown up, too.

Candyfreak is the delicious story of one man's lifelong obsession with candy and his quest to discover its origins in America.

|

The author will now rationalize

The answer is that we don't choose our freaks, they choose us.

I don't mean this as some kind of hippy dippy aphorism about the power of fate. We may not understand why we freak on a particular food or band or sports team. We may have no conscious control over our allegiances. But they arise from our most sacred fears and desires and, as such, they represent the truest expression of our selves.

In my case, I should start with my father, as all sons must, particularly those, like me, who grew up in a state of semithwarted worship.

Richard Almond: eldest son to the sensationally famous political scientist Gabriel Almond, husband to the lovely and formidable Mother Unit (Barbara), father to three sons, esteemed psychiatrist, author, singer, handsome, brilliant, yes, check, check, check, expert maker of candles and jam, weekend gardener, by all measures (other than his own) a stark, raving success. This was my dad on paper. In real life, he was much harder to figure out, because he didn't express his feelings very much, because he had come from a family in which emotional candor was frowned upon. So I took my clues where I could find them. And the most striking one I found was that he had an uncharacteristic weakness for sweets, that he was, in his own still-waters-run-deep kind of way, a candyfreak.

I loved that I would find my dad, on certain Saturday afternoons, during the single hour each week that his presence wasn't required elsewhere, making fudge in the scary black cast-iron skillet kept under the stove. I loved how he used a toothpick to test the consistency of the fudge and then gave the toothpick to me. I loved the fudge itself-dense, sugary, with a magical capacity to dissolve on the tongue.

Following his lead, I even made a couple of efforts to cook up my own candy. I would cite the Cherry Lollipop Debacle of 1976 as the most memorable, in that I came quite close to creating actual lollipops, if you somewhat broaden your conception of lollipops to include little red globs of corn syrup that stick to the freezer compartment in such a manner as to cause the Mother Unit to weep.

I loved that my dad was himself obsessed with marzipan (though I did not love marzipan). I loved his halvah habit (though I did not love halvah). I loved that he bought chocolate-covered graham crackers when he went shopping, and I do not mean the tragic Keebler variety, which are coated in a waxy, synthetic-chocolate coating that exudes a soapy aftertaste. I mean the original, old-school brand, covered in dark chocolate and filled not with an actual graham cracker, but with a lighter, crispier biscuit distinguished by its wheaty musk. I loved that my father would, after certain meals-say, those meals in which none of his sons threatened to kill another-give me a couple of bucks and send me to the Old Barrel to buy everyone a candy bar. What a sense of economic responsibility! Of filial devotion! I loved that my father chose Junior Mints and I loved how he ate them, slipping the box into his shirt pocket and fishing them out, one by one, with the crook of his index finger. I loved watching him eat these, patiently, with moist clicks of the tongue. I loved his mouth, the full, pillowy lips, the rakishly crooked teeth-the mouth of a closet sensualist.

It is worth noting the one story about my father's childhood that I remember most vividly, which is that his father used to send him out on Sunday mornings with six cents to get the New York Times, and that, on certain days, if he were feeling sufficient bravado, he would lose a penny down the sewer and buy a nickel pack of Necco wafers instead. This tale astounded me. Not only did it reveal my father as capable of subterfuge, but it suggested candy as his instrument of empowerment. (In later years, as shall be revealed, I myself became a prodigious shoplifter, though I tend to doubt that the legal authorities would deem the above facts exculpatory.)

The bottom line here is that candy was, for my father and then for me, one of the few permissible forms of self-love in a household that specialized in self-loathing. It would not be overstating the case to suggest that we both used candy as a kind of antidepressant.

There were other factors in play:

Oral Fixation-It is certainly possible that there is a person out there more orally fixated than me. I would not, however, want to meet him or her. We begin with thumbsucking. Oh yes. Devout thumbsucker, years zero to ten. I don't remember how I was weaned from this habit, though it was probably around the time my older brother, Dave, asked me if I wanted to feel something "really cool," then told me to put my hands behind my back and rubbed my thumbs with what felt like an oily towelette but was, in fact, a hot chili plucked from the ristra hanging in our kitchen, which I discovered immediately upon sticking my thumb in my mouth. I was rendered speechless for the next four hours.

So I kicked the thumb but took up lollipops, gum, Lick-A-Stix, hard candies, and Fruit Rolls, which I used to wrap around my fingers and suck until my knuckles turned pruney. I still bite my nails to the quick. I've chewed through a forest of toothpicks. I've even tried to take up smoking. I frequently feel the desire to bite attractive women, not just in moments of amour, but in elevators, restaurants, subways.

I don't think of this as particularly strange. Babies, after all, learn to interact with the world through their mouths. For a good year or so-before their parents start hollering at them not to put things in their mouths-all they do is put things in their mouths. Perhaps my folks failed to yell this at me enough, because I still take on the world mouth-first, and I think about the experience of the world in my mouth all the time. (I am certain, by the way, that there is some really cool German word for this idea of the world in my mouth, something along the lines of zietschaungundermoutton, and if this were the sort of book that required actual research, I would consult my father, who speaks German.) What I mean by this is that I imagine what it would be like to lick or chew or suck a great deal of stuff. Examples would include the skin of a killer whale, any kind of bright acrylic paint, and Cameron Diaz's eyeballs.

I practice a good deal of mouthplay.

If, for instance, I happened to be eating a Jolly Rancher Cherry Stick, which I happened to be doing for much of my youth, I would gradually shape the candy into a quasi retainer. This was done by warming the piece until malleable, then pressing it up into my palate with my tongue. At a certain point, this habit morphed into an ardent belief that I could use candy to straighten my teeth, which were (and are) crooked. This was not such a crazy idea. Braces, after all, operated on the basic principle that if pushed hard enough, teeth would move. So I spent most of fifth and sixth grades with a variety of hard candies lodged between my upper teeth. Charm's Blow Pops were most effective for this purpose, because they had a stick and could thus be removed voluntarily.

The Whole Name Thing-You will have noticed by this time, that I have a distinctly candyfreakish name. This is not my fault. All credit or blame should be directed to my paternal great-grandfather, the Rabbi David Pruzhinski (blessed be his memory), who came from the region of Pruzhini to London around 1885 and changed his name to Almond. Why Almond? The official explanation is steeped in academic ambition. David took secular classes during the day then raced off to attend rabbinical classes at night. The professors at his college posted grades and assignments in alphabetical order. So he needed a new name that began with a letter at the beginning of the alphabet. No one knows why he settled on Almond over, say, Adams. There has been speculation that he was the victim of a prank. Or that he chose Almond because the almond tree is frequently mentioned in the Old Testament. Whatever the reason, I was saddled with this strange name, which meant that I was constantly, constantly, being serenaded with the sometimes you feel like a nut Almond Joy/Mounds jingle, which I would have liked to quote in full, except that Hershey's legal staff denied me permission. I can certainly understand why. God only knows what ruin might befall Hershey if this jingle-which hasn't been used in two decades-were suddenly brazenly resurrected by a young Jewish candyfreak. One shudders to consider the fallout for the entire fragile candy-jingle-trademark ecosystem. The company was, however, thoughtful enough to include in its letter of refusal a coupon for a dollar off any Hershey product-Twizzlers included!-which certainly went a long way toward restoring my faith in corporate America.

I should note that the success of this particular jingle was an undying source of fascination to me and especially irksome because I didn't even like almonds as a kid and absolutely loathed coconut, an enmity which will be discussed further on. I'm not suggesting that my identity was determined by something as random as my last name, just as I wouldn't suggest that those with the last name Miller will grow up with a predilection for cheap beer. But there is no doubt that having a name associated with candy was a contributing factor. So was the date of my birth, October 27, a mere four days before the Freak National Holiday. And one other fact that I have come to regard as eerie: for virtually my entire childhood our family lived on a street called Wilkie Way.

Freak Physiology-I have been endowed with one of those disgusting metabolisms that allow me to eat at will. To physiologists, I am a classic ectomorph, though my ex-girlfriends have tended to gravitate toward the term scrawny. The downside of this metabolic arrangement is that I am a slave to my blood sugar. If I don't eat for too long, I start thinking about murdering people, and I am inexorably drawn toward fats and carbs. I hate most vegetables, particularly what I call the evil brain trio-broccoli, cauliflower...

|

|

| View all 5 comments |

Amazon.com (MSL quote), USA

<2008-02-26 00:00>

Picture a magical, sugar-fueled road trip with Willy Wonka behind the wheel and David Sedaris riding shotgun, complete with chocolate-stained roadmaps and the colorful confetti of spent candy wrappers flying in your cocoa powder dust. If you can imagine such a manic journey - better yet, if you can imagine being a hungry hitchhiker who's swept through America's forgotten candy meccas: Philadelphia (Peanut Chews), Sioux City (Twin Bing), Nashville (Goo Goo Cluster), Boise (Idaho Spud) and beyond--then Candyfreak: A Journey through the Chocolate Underbelly of America, Steve Almond's impossible-to-put down portrait of regional candy makers and the author's own obsession with all-things sweet, would be your Fodor's guide to this gonzo tour.

With the aptly named Almond (don't even think of bringing up the Almond Joy bit - coconut is Almond's kryptonite), obsession is putting it mildly. Almond loves candy like no other man in America. To wit: the author has "three to seven pounds" of candy in his house at all times. And then there's the Kit Kat Darks incident; Almond has a case of the short-lived confection squirreled away in an undisclosed warehouse. "I had decided to write about candy because I assumed it would be fun and frivolous and distracting," confesses Almond. "It would allow me to reconnect to the single, untarnished pleasure of my childhood. But, of course, there are no untarnished pleasures. That is only something the admen of our time would like us to believe." Almond's bittersweet nostalgia is balanced by a fiercely independent spirit--the same underdog quality on display by the small candy makers whose entire existence (and livelihood) is forever shadowed by the Big Three: Hershey's, Mars, and Nestle.

Almond possesses an original, heartfelt, passionate voice; a writer brave enough to express sheer joy. Early on his tour he becomes entranced with that candy factory staple, the "enrober"- imagine an industrial-size version of the glaze waterfall on the production line at your local Krispy Kreme, but oozing chocolate--dubbing it "the money shot of candy production." And while he writes about candy with the sensibilities of a serious food critic (complimenting his beloved Kit Kat Dark for its "dignified sheen," "puddinglike creaminess," "coffee overtones," and "slightly cloying wafer") words like "nutmeats" and "rack fees" send him into an adolescent twitter.

...the Marathon Bar, which stormed the racks in 1974, enjoyed a meteoric rise, died young, and left a beautiful corpse. The Marathon: a rope of caramel covered in chocolate, not even a solid piece that is, half air holes, an obvious rip-off to anyone who has mastered the basic Piagetian stages, but we couldn't resist the gimmick. And then, as if we weren't bamboozled enough, there was the sleek red package, which included a ruler on the back and thereby affirmed the First Rule of Male Adolescence: If you give a teenage boy a candy bar with a ruler on the back of the package, he will measure his dick.

Candyfreak is one of those endearing, quirky titles that defy swift categorization. One of those rare books that you'll want to tear right through, one you won't soon stop talking about. And eager readers beware: It's impossible to flip through ten pages of this sweet little book without reaching for a piece of chocolate. -Brad Thomas Parsons

|

Publishers Weekly (MSL quote), USA

<2008-02-26 00:00>

The appropriately named Almond goes beyond candy obsession to enter the realm of "freakdom." Right up front, he divulges that he has eaten a piece of candy "every single day of his entire life," "thinks about candy at least once an hour" and "has between three and seven pounds of candy in his house at all times." Indeed, Almond's fascination is no mere hobb - it's taken over his life. And what's a Boston College creative writing teacher to do when he can't get M&Ms, Clark Bars and Bottle Caps off his mind? Write a book on candy, of course. Almond's tribute falls somewhere between Hilary Liftin's decidedly personal Candy and Me and Tim Richardson's almost scholarly Sweets: A History of Candy. There are enough anecdotes from Almond's lifelong fixation that readers will feel as if they know him (about halfway through the book, when Almond is visiting a factory and a marketing director offers him a taste of a coconut treat, readers will know why he tells her, "I'm really kind of full - he hates coconut). But there are also enough facts to draw readers' attention away from the unnaturally fanatical Almond and onto the subject at hand. Almond isn't interested in "The Big Three" (Nestle, Hershey's and Mars). Instead, he checks out "the little guys," visiting the roasters at Goldenberg's Peanut Chews headquarters and hanging out with a "chocolate engineer" at a gourmet chocolate lab in Vermont. Almond's awareness of how strange he i - the man actually buys "seconds" of certain candies and refers to the popular chocolate mint parfait as "the Andes oeuvre" - is strangely endearing.

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. |

AudioFile (MSL quote), USA

<2008-02-26 00:00>

If you're dieting or diabetic, avoid this audiobook. The descriptions of huge machines extruding chocolate bars and the smell of roasting nuts would cause any such person agony until satisfied with a forbidden fix. Oliver Wyman's enthusiasm and ecstasy convey every sensual delight the author intends as he describes extinct and existing candy - its shape, color, consistency, and aroma. Starting with the author's childhood memories of sinful snacks, the story moves to a visit with the world's candy bar expert, the collector of 20,000 confection wrappers and author of two forgotten books. The work also features tours of factories and tasty biographies of the inventors of wonderful sweets we've all had on our tongues. J.A.H. © AudioFile 2004, Portland, Maine - Copyright © AudioFile, Portland, Maine |

Booklist (MSL quote), USA

<2008-02-26 00:00>

Anyone who has ever really savored a piece of candy and appreciates more than its mere sweetness will sympathize with Almond's obsession. Much of the source of this addiction appears to stem from his psychiatrist father, who had a similar fixation. Then, of course, there is that surname, which his Polish immigrant grandfather took mostly as a way to ensure that he'd sort alphabetically to the top. Whatever its origins, Almond's passion for candy, chocolate or otherwise, leads him to inventory the various sweetmeats he has encountered throughout his life. He attempts to visit candy factories to back up his appetite with fact, but he discovers how very secretive candy manufacturers can be. He does achieve a tour of Pittsburgh's Clark bar factory, and there Almond finds out just how far the freshly made product surpasses the candy bar that has been sitting on a grocer's shelf. The decidedly regional nature of American candy production takes Almond to all sorts of destinations where he encounters those tastefully inventive minds who satisfy the country's sweet tooth. Mark Knoblauch

Copyright © American Library Association. All rights reserved |

View all 5 comments |

|

|

|

|