|

|

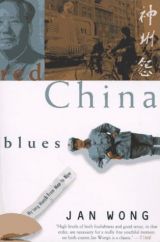

Red China Blues: My Long March From Mao to Now (Paperback)

by Jan Wong

| Market price: ¥ 268.00

MSL price:

¥ 248.00

[ Shop incentives ]

|

| Stock:

Pre-order item, lead time 3-7 weeks upon payment [ COD term does not apply to pre-order items ] |

MSL rating:

Good for Gifts Good for Gifts |

| If you want us to help you with the right titles you're looking for, or to make reading recommendations based on your needs, please contact our consultants. |

Detail |

Author |

Description |

Excerpt |

Reviews |

|

|

|

Author: Jan Wong

Publisher: Anchor

Pub. in: May, 1997

ISBN: 0385482329

Pages: 416

Measurements: 8.1 x 5.5 x 1.2 inches

Origin of product: USA

Order code: BA01124

Other information: ISBN-13: 978-0385482325

|

|

Rate this product:

|

|

- MSL Picks -

Jan Wong,a Canadian journalist of Chinese ancestry, in this illuminating volume writes of her experiences as an ardent young Maoist in the early 1970's who actually went to China to work and study.

She hauled pig manure in a Chinese re-education farm, and at Beijing University she turned in a fellow student who had begged her help to escape to the West.

Slowly she realized the evil of the Communist system in China and was repatriated to the West in 1978.

Wong returned years later as an undercover journalist to China where she covered the Tianmen Square Massacre, in which three thousand pro-democracy students were mowed down in cold blood by Red China's army, on the orders of dictator, Jian Zemin.

She also covered China's contradictory development into a capitalist state under a Communist dictatorship, or a Communist dictatorship with a capitalist economy...akin to Fascism!

She covers the Tianmen Square Massacre of 1989, letting the the reader know of some of the lesser known details, and how the Communist army opened fire on the students after they began leaving the square:

"A [...]girl was killed and they just brought her body back...After the third barrage I counted more than twenty bodies. One cyclist was shot in the back right below our balcony. There were two big puddles of blood on the Avenue of Eternal Peace. People carried the body of a little girl towards the back of the hotel. After twenty three more minutes, a few people gathred up enough courage to aproach the wounded. The soldiers let loose another blast, sending the would be rescuers scurrying for cover. The crowd was enraged. I grimly kept track of the time. An hour later, the wounded were still on the ground, bleeding to death.

She speaks of the great poverty of the new Red China, with inequalities far greater than anything in the liberal democracies of the world, and crushing poverty in the rural provinces. Despite economic changes, China remains a brutal dictatorship, with no political liberalization or democratization having been allowed by the iron grip of the Communist Party.

Peeople are still opresed in day-to-day life. People are not allowed to own dogs, and to deal with a fad of people acquiring dogs as pets in the early 1990s, special police squads swept through the neigbourhoods, strangling dogs with steel wire looped at the end of metal poles.

The author recounts some regret at buying into the Communist lie, with the realization that "The Western world, especially Canada, is far more socialistic than China has ever been, with it's free public education, universal medicare, unemployment insurance, and government funding for television ads against domestic violence. China has made me appreciate my own country, with it's tiny ethnically diverse population of unassuming donut-eaters. I had gone all the way to China to find an idealistic revolutionary society, when I already had it right to home."

She ends of on a positive note, predicting, in 1997, a great change in China , and the death of the Communist Party, and real democracy.

Ten years later, this is not close to being realized, with a tightening of political control by the Communist dictatorship having taken place.

Despite being one of the most brutal dictatorships on this planet, China has gained international acceptibility, without improving democracy or human rights!

Nobody bats an eyelid at the Olympic Games for 2008 being set in Beijing.

The worst abuses of the Communist regime has it's apologists in the WEst.

The Stalinist Workers World Party in North America, (which has praised Stalinism in the Soviet Union, and applauded suicide bombings against Jewish women and chidren in Israel) congratulated the Chinese regime after the Tianmen Square Massacre, for having 'won a battle against imperialist and counter-revolutionary forces."

The fact that such sentiments can be uttered makes one wonder how far the world has actually come.

(From quoting Gary Selikow, USA)

|

|

Jan Wong was the Beijing correspondent for the Toronto Globe and Mail from 1988 to 1994. She is a graduate of McGill University and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, and is the recipient of the George Polk Award, and other honors for her reporting. Wong has written for The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal, among many other publications in the United States and abroad. She lives in Toronto.

|

|

From Publisher

Jan Wong, a Canadian of Chinese descent, went to China as a starry-eyed Maoist in 1972 at the height of the Cultural Revolution. A true believer-and one of only two Westerners permitted to enroll at Beijing University-her education included wielding a pneumatic drill at the Number One Machine Tool Factory. In the name of the Revolution, she renounced rock & roll, hauled pig manure in the paddy fields, and turned in a fellow student who sought her help in getting to the United States. She also met and married the only American draft dodger from the Vietnam War to seek asylum in China.

Red China Blues is Wong's startling - and ironic- - memoir of her rocky six-year romance with Maoism (which crumbled as she became aware of the harsh realities of Chinese communism); her dramatic firsthand account of the devastating Tiananmen Square uprising; and her engaging portrait of the individuals and events she covered as a correspondent in China during the tumultuous era of capitalist reform under Deng Xiaoping. In a frank, captivating, deeply personal narrative she relates the horrors that led to her disillusionment with the "worker's paradise." And through the stories of the people - an unhappy young woman who was sold into marriage, China's most famous dissident, a doctor who lengthens penises - Wong reveals long-hidden dimensions of the world's most populous nation.

In setting out to show readers in the Western world what life is like in China, and why we should care, she reacquaints herself with the old friends - and enemies of her radical past, and comes to terms with the legacy of her ancestral homeland.

|

Ten days after my reprieve, Cadre Huang surprised us by announcing we were going to the Beijing Number One Machine Tool Factory for fifty days of labor. Erica and I let out a cheer. We had been lobbying for months for a chance at thought reform. For foreign students like us, hard labor was an honor. In my case in particular, it meant I was no longer persona non grata.

According to Mao, everyone needed physical labor. For class enemies, it was a punishment. For ordinary people, it was an inoculation against bourgeois thinking. For intellectuals, sweating with the proletariat was both a punishment and a prophylactic. In one year, Scarlet’s class had already been through mandatory stints of kaimen banxue, or open-door schooling, at a farm, a factory, a seaport and a military base.

The Number One Machine Tool Factory, which made lathes, was one of six model factories directly under the political control of Mao and his radical wife. In 1950, Mao had sent his eldest son there to work incognito as deputy Party secretary. In 1966, Number One was the factory considered politically reliable enough to send Workers Propaganda Teams into Beijing University.

Erica, our teachers and I shared one small room in a dingy workers’ dormitory. The toilet stalls down the hall were so disgusting I learned to breathe through my mouth. Each morning, we ignored the first, ear-splitting 5 a.m. bell and got up with the 6 a.m. one. We washed in groggy silence, then donned coarse work suits, stiff denim caps and canvas work gloves with seams so thick they gave me blisters. It was still dark when we stumbled outside to board a city bus for the fifteen-minute ride to the factory.

Number One, a sprawling collection of low-lying ugly brick buildings in southeast Beijing, was originally a munitions factory. The Chinese government saw to it that the proletariat lived better than intellectuals. As “workers,” we now could shower every day, instead of just twice a week. And unlike the slop served at the Big Canteen, the factory dining halls provided a wide selection of dumplings, noodles, breads and stir-fried dishes.

I was “apprenticed” to Master Liu, a fortyish man with a perpetually anxious look on his face, probably because he was supposed to teach me how to use a lathe. According to socialist etiquette, I called him Master Liu and he called me Little Wong. He had typical class-enemy looks - sallow skin, shifty eyes and a scrawny build - but in fact he was a kindly man with a mania for playing basketball. Under his influence, I joined the women’s team, where my towering five-foot, three-inch height was an asset.

In the middle of the first afternoon, Master Liu told me to start tidying up to get ready for a political meeting. Wiping the gunk off my hands with oily rags, I was beside myself with excitement; Beijing University had always barred me from political study. I joined about a dozen workers sitting in a circle on little folding stools. A middle-aged worker cleared his throat. “Today we are going to discuss with what attitude we should receive the opening of Beijing’s Sixth Labor Union Congress. Please, everyone actively speak out.”

I looked around expectantly. Granted, it wasn’t the world’s sexiest topic, but what would the proletariat have to say? Nothing, it turned out. There was an awkward silence. Finally, a young worker in stained denim spoke up.

"Uh, uh, the proletariat, uh, um, the dictatorship of the proletariat, er, the proletariat is the leading class. It must lead everything.” He stopped, unsure of what to say next. He reddened slightly.

"Speak out,” said the middle-aged worker, nodding encouragingly.

"Uh, well, I think the way we should receive the opening of Beijing’s Sixth Labor Union Congress is to, ah, um, study Marxism! Study Marxism-Leninism! Yes, to correctly receive the opening we must study Marxism-Leninism,” he said. He sat back, looking relieved. Others, all men, began to talk in monotones. Many stared at the patch of concrete floor in front of them. The first worker had set the tone. Each speaker exhorted everyone else to study Marxism-Leninism. Even I felt my eyes glazing over. When the discussion leader finally announced the meeting was over, people bolted for the door.

That first night, waiting in line in the canteen, I spotted a commotion ahead of me. Two young men had faced off, their noses inches apart.

"You turtle’s egg!” one of them screamed, using the ancient Chinese word for bastard.

"I fuck your mother’s cunt!” the other yelled back, using a more contemporary phrase.

At that, the motherfucker slapped the turtle’s egg, who responded by heaving a bowl of steaming dumplings in the other’s face. Someone threw a punch, and they began fighting in earnest until bystanders pulled them apart. I had a feeling my Chinese was going to take a great leap forward at the factory.

|

|

| View all 11 comments |

Publishers Weekly, USA

<2008-01-08 00:00>

This superb memoir is like no other account of life in China under both Mao and Deng. Wong is a Canadian ethnic Chinese who, in 1972, at the height of the cultural revolution, was one of the first undergraduate foreigners permitted to study at Beijing University. Filled with youthful enthusiasms for Mao's revolution, she was an oddity: a Westerner who embraced Maoism, appeared to be Chinese and wished to be treated as one, although she didn't speak the language. She set herself to become fluent, refused special consideration, shared her fellow-students rations and housing, their required stints in industry and agriculture and earnestly tried to embrace the Little Red Book. Although Wong felt it her duty to turn in a fellow student who asked for help to emigrate to the West, she could not repress continual shock at conditions of life, and by the time she was nearly expelled from China for an innocent friendship with a "foreigner," much of her enthusiasm, which lasted six years, had eroded. In 1988, returning as a reporter for the Toronto Globe Mail, she was shocked once again, this time by the rapid transformations of the society under Deng's exhortation: "to be rich is glorious." Her account is informed by her special background, a cold eye, a detail. Her description of the events at Tiananmen Square, which occurred on her watch, is, like the rest of the book, unique, powerful and moving.

Copyright 1996 Reed Business Information, Inc. -This text refers to the Hardcover edition.

|

Kirkus Reviews, USA

<2008-01-08 00:00>

A crackerjack journalist's (she's a George Polk Award winner) immensely entertaining and enlightening account of what she learned during several extended sojourns in the People's Republic of China. A second-generation Canadian who enjoyed a sheltered, even privileged, childhood in Montreal, Wong nonetheless developed a youthful crush on Mao Zedong's brand of Communism. She first visited China in 1972 on summer holiday from McGill University. Although the PRC was still convulsed by the so-called Cultural Revolution, the starry-eyed author enrolled in Beijing University and remained in the country for 15 months. Emotionally bloodied but unbowed by quotidian contact with the harsher realities of Maoism, Bright Precious Wong (as she was known to fellow students and party cadres) mastered Chinese and searched for ways to express solidarity with the masses. Leaving the PRC only long enough to earn a degree from McGill, the author returned in the fall of 1974 for a lengthy stay that made her increasingly aware of Chinese Communism's contradictions and evils.

Disturbing encounters with dissidents raised her consciousness of the regime's oppressive policies. Although her zeal diminished, Wong soldiered on, eventually acquiring an American spouse (perhaps the only US draft dodger to seek asylum in the PRC) and a correspondent's job with the New York Times. When President Carter pardoned Vietnam War resisters, the author and her husband came back to North America. She returned to China in 1988 as the Beijing bureau chief of The Toronto Globe & Mail. Experiencing something akin to culture shock at the changes wrought by Deng Xioaping's capitalist-road programs, Wong was an eyewitness to the bloody Tiananmen Square confrontation. She ferreted out long-suppressed truths about penal colonies, the use of prisoners as unpaid laborers, and the public execution of criminals. Tellingly detailed recollections of the journeys of an observant and engaged traveler through interesting times. (Author tour)

Copyright ©1996, Kirkus Associates, LP. All rights reserved. -This text refers to the Hardcover edition.

|

The Gazette , USA

<2008-01-08 00:00>

A marvellous book by one of Canada’s best-ever foreign correspondents at the top of her form. |

The Globe and Mail, USA

<2008-01-08 00:00>

Totally captivating. A wonderful memoir. |

View all 11 comments |

|

|

|

|