|

|

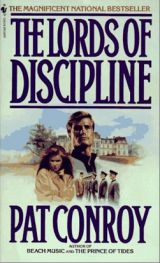

The Lords of Discipline (Paperback)

by Pat Conroy

| Category:

Fiction |

| Market price: ¥ 108.00

MSL price:

¥ 98.00

[ Shop incentives ]

|

| Stock:

In Stock |

MSL rating:

Good for Gifts Good for Gifts |

| MSL Pointer Review:

A haunting classic. Conroy’s combination of precise military cadence and southern gothic prose is just mind-boggling. |

| If you want us to help you with the right titles you're looking for, or to make reading recommendations based on your needs, please contact our consultants. |

Detail |

Author |

Description |

Excerpt |

Reviews |

|

|

|

Author: Pat Conroy

Publisher: Bantam; Reissue edition

Pub. in: December, 1985

ISBN: 0553271369

Pages: 512

Measurements: 7.2 x 4.4 x 1.4 inches

Origin of product: USA

Order code: BA00469

Other information:

|

|

Rate this product:

|

|

- Awards & Credential -

A Magnificent National Bestseller in North America. |

|

- MSL Picks -

Author Pat Conroy borrowed heavily from his experiences as a cadet at the Citadel to pen this 1980 novel, The Lords of Discipline. Later made into a film version of the same name that played up the subplot of racism at the expense of the greater themes of friendship, loyalty, discipline, and southern atmosphere, this book is a penetrating insight into the rigors of life in a military college. Most readers are probably more familiar with Pat Conroy's novels The Great Santini and The Prince of Tides, and the two movies they spawned, but fans of those books shouldn't overlook this phenomenal effort.

Conroy's protagonist in The Lords of Discipline is one Will McLean, a cadet in the senior class at the Carolina Military Institute (referred to by everyone associated with it as "The Institute") in the late 1960s. It is easy to imagine that McLean is a symbolic Conroy, with his love of English and writing, his liberal ideas, and his sense of individuality within an institution that subscribes to total conformity. Born in Georgia, Will agreed to attend CMI when his father asked him to do so on his deathbed. It is only because of this promise that Will sticks it out through what ranks as one of the most degrading, brutal experiences a person will ever face. It is the freshman year at the Institute that really separates the wheat from the chaff, so to speak, as all incoming plebes (called knobs by upperclassmen) undergo hazing of astonishing, and illegal, levels. McLean survives the ordeal by making friends with Tradd St. Croix, a rich scion of one of Charleston's most prominent families; Dante Pignetti, a tough as nails northerner who lifts weights and possesses a most unusual affection for his girlfriend Theresa; and Mark Santoro, another northerner who matches Pignetti in physical prowess. The four friends latch on to one another during freshman year and then share the rest of their school days as roommates. The Institute's rigorous requirements create emotional bonds that go beyond mere friendship: these guys are like brothers, and they openly profess their love for one another without any sense of indecency.

Will might have cleared the final hurdles of his senior year and graduated in relative anonymity if several incidents didn't rise up to confront him. The first problem occurs when Colonel Berrineau, known as "Bear," the gruff overseer and protector of the cadets, asks Will to protect the first black plebe in the school's history. Another crisis arises when Will meets a local girl, a well to do lass suffering from an unwanted pregnancy. These two incidents, along with Will's increasing sense of alienation from the Institute's mindless conformity, place McLean's standing at school in deep jeopardy. When a secret organization within the school called "The Ten" decides that the black cadet must go, Will finds himself in a moral dilemma that forces him to decide where his loyalties lie. McLean's ultimate choices cast doubts on the certitude of honor and the dangers of conformity.

Even this lengthy summary doesn't properly convey the numerous themes and memorable scenes spread throughout this story. Conroy is a fantastic writer, creating situation after situation of penetrating insights, moral and emotional predicaments, and youthful vigor. Not many writers can pull off a story like the one about Will's last basketball game at the Institute. Conroy perfectly captures the triumph and tragedy of a young man playing the last game of a sport he loves. Moreover, the author uses the game as a way to expose McLean's agonizing dilemma about the Institute. In many ways, Will despises what the Institute stands for, how it demeans and crushes the human spirit, but during the game he realizes how great it is to have the entire body of cadets pulling for him with all of their heart. It's this love/hate relationship with the CMI that makes Will's final decisions so achingly difficult.

Arguably the best part of The Lords of Discipline involves Will's flashback concerning his freshman year experiences as a knob. I know nothing about life in a military institution, but the situations Will and his friends found themselves in are shocking and brutal. It all starts with "Hell Night," where the cadets march the knobs to the parade ground and proceed to scream and bully until every new man is reduced to a quivering wreck. This night of torture is only the beginning of a long year of endless brutality and sadism. All suffer endlessly under the system, but cadets pay special attention to certain individuals who show any signs of weakness. In a process described as "taming," a knob with an allergy to tomatoes resigns after cadets force him to drink glass after glass of tomato juice. I don't know if this type of behavior continues today, but it must have been the case when Conroy attended the Citadel. Personally, I do think this sort of weeding out process is a good idea, as discipline and toughness tend to be in short supply today. At the same time, some of the stuff Conroy describes in his novel is definitely in the region of pure illegality. It's just another example of the split personality of an institute that touts honor above all else while engaging in decidedly dishonorable activities.

Everything you can think of is in this book: romance, action, and drama all make appearances here. Conroy leaves little to the imagination as he sweeps his readers away through page after page of pure genius. I'll bet the Citadel never knew they had a brilliant artist strolling through their hallowed halls, but readers are better off that Conroy suffered the slings and arrows of a military institute. The Lords of Discipline is must read material.

(From quoting Jeffrey Leach, USA)

Target readers:

General readers

|

|

- Better with -

Better with

The Prince of Tides

:

|

|

Customers who bought this product also bought:

|

The Prince of Tides (Paperback)

by The Prince of Tides

Conroy’s writing takes you places with beautiful prose, and his depth of character only makes you feel empathy in times of sorrow, and joy in the good times. |

|

The Lords of Discipline (Paperback)

by Pat Conroy

A haunting classic. Conroy’s combination of precise military cadence and southern gothic prose is just mind-boggling. |

|

Beach Music (Paperback)

by Pat Conroy

Beautiful writing, gripping characters, a book showing why Conroy has been regarded as America’s most beloved storyteller.

|

|

The Great Santini (Paperback)

by Pat Conroy

A wonderful author who brings his characters to life with a grace, humanity and humor rarely seen in modern literature. |

|

|

Pat Conroy is the bestselling author of The Water is Wide, The Great Santini, The Lords of Discipline, The Prince of Tides, and Beach Music. He lives in Fripp Island, South Carolina.

|

|

From the Publisher:

A novel you will never forget...

This powerful and breathtaking novel is the story of four cadets who have become bloodbrothers. Together they will encounter the hell of hazing and the rabid, raunchy and dangerously secretive atmosphere of an arrogant and proud military institute. They will experience the violence. The passion. The rage. The friendship. The loyalty. The betrayal. Together, they will brace themselves for the brutal transition to manhood... and one will not survive.

With all the dramatic brilliance he brought to The Great Santini, Pat Conroy sweeps you into the turbulent world of these four friends - and draws you deep into the heart of his rebellious hero, Will McLean, an outsider forging his personal code of honor, who falls in love with a whimsical beauty... and who undergoes a transition more remarkable then he ever imagined possible.

|

Chapter One

When I crossed the Ashley River my senior year in my gray 1959 Chevrolet, I was returning with confidence and even joy. I'm a senior now, I thought, looking to my right and seeing the restrained chaste skyline of Charleston again. The gentleness and purity of that skyline had always pleased me. A fleet of small sailboats struggled toward a buoy in the windless river, trapped like pale months in the clear amber of late afternoon.

Then I looked to my left and saw, upriver, the white battlements and parapets of Carolina Military Institute, as stolid and immovable in reality as in memory. The view to the left no longer caused me to shudder involuntarily as it had the first year. No longer was I returning to the cold, inimical eyes of the cadre. Now the cold eyes were mine and those of my classmates, and I felt only the approaching freedom that would come when I graduated in June. After a long childhood with an unbenign father and four years at the Institute, I was looking forward to that day of release when I would no longer be subject to the fixed, irresistible tenets of martial law, that hour when I would be presented with my discharge papers and could walk without cadences for the first time.

I was returning early with the training cadre in the third week of August. It was 1966, the war in Vietnam was gradually escalating, and Charleston had never looked so beautiful, so untouchable, or so completely mine. Yet there was an oddity about my presence on campus at this early date. I would be the only cadet private in the barracks during that week when the cadre would prepare to train the incoming freshmen. The cadre was composed of the highest-ranking cadet officers and non-coms in the corps of cadets. To them fell the serious responsibility of teaching the freshmen the cheerless rudiments of the fourth-class system during plebe week. The cadre was a diminutive regiment of the elite, chosen for their leadership, their military sharpness, their devotion to duty, their ambition, and their unquestioning, uncomplicated belief in the system.

I had not done well militarily at the Institute. As an embodiment of conscious slovenliness, I had been a private for four consecutive years, and my classmates, demonstrating remarkable powers of discrimination, had consistently placed me near the bottom of my class. I was barely cadet material, and no one, including me, ever considered the possibility of my inclusion on the cadre.

But in my junior year, the cadets of fourth battalion had surprised both me and the Commandant's Department by selecting me as a member of the honor court, a tribunal of twenty-one cadets known for their integrity, sobriety, and honesty. I may not have worn a uniform well, but I was chock full of all that other stuff. It was the grim, excruciating duty of the honor court to judge the guilt or innocence of their peers accused of lying, stealing, cheating, or of tolerating those who did. Those found guilty of an honor violation were drummed out of the Corps in a dark ceremony of expatriation that had a remorseless medieval splendor about it.

Once I had seen my first drumming-out, it removed any temptation I might have had to challenge the laws of the honor code. The members of the court further complicated my life by selecting me as its vice chairman, a singularly indecipherable act that caused me a great deal of consternation, since I did not even understand my election to that cold jury whose specialty was the killing off of a boy's college career. By a process of unnatural selection, I had become one of those who could summon the Corps and that fearful squad of drummers for the ceremony of exile. Since I was vice chairman of the court, the Commandant's Department had ordered me to report two weeks before the arrival of the regular Corps.

In my senior year, irony had once again gained a foothold in my life, and I was a member of the training cadre. Traditionally, the chairman and vice chairman explained the rules and nuances of the honor system to the regiment's newest recruits. Traditionally, the vice chairman had always been a cadet officer, but even at the Institute tradition could not always be served. Both tradition and irony have their own system of circulation, their own sense of mystery and surprise.

I did not mind coming back for cadre. Since my only job was to introduce the freshmen to the pitfalls and intricacies of honor, I was going to provide the freshmen with their link to the family of man. Piety comes easily to me. I planned to make them laugh during the hour they were marched into my presence, to crack a few jokes, tell them about my own plebe year, let them relax, and if any of them wanted to, catch up on the sleep they were missing in the barracks. The residue of that long, sanctioned nightmare was still with me, and I wanted to tell these freshmen truthfully that no matter how much time had elapsed since that first day at the Institute, the one truth the system had taught me was this: A part of me would always be a plebe.

I pulled my car through the Gates of Legrand and waited for the sergeant of the guard to wave me through. He was conferring with the Cadet Officer of the Guard, who looked up and recognized me.

"McLean, you load," Cain Gilbreath said, his eighteen-inch neck protruding from his gray cotton uniform shirt.

"Excuse me, sir," I said, "but aren't you a full-fledged Institute man? My, but you're a handsome, stalwart fellow. My country will always be safe with men such as you."

Cain walked up to my car, put his gloved hand against the car, and said, "There was a rumor you'd been killed in an auto wreck. The whole campus is celebrating. How was your summer, Will?"

"Fine, Cain. How'd you pull guard duty so early?"

"Just lucky. Do you have religious beliefs against washing this car?" he asked, withdrawing his white glove from the hood. "By the way, the Bear's looking for you."

"What for?"

"I think he wants to make you regimental commander. How in the hell would I know? What do you think about the big news?"

"What big news?"

"The nigger."

"That's old news, and you know what I think about it."

"Let's have a debate."

"Not now, Cain," I said, "but let's go out for a beer later on in the week."

"I'm a varsity football player," he said with a grin, his blue eyes flashing. "I'm not allowed to drink during the season."

"How about next Thursday?"

"Fine. Good to see you, Will. I've missed trading insults with you." I drove the car through the Gates of Legrand for my fourth and final year. I realized that the Institute was now a part of my identity. I was nine months away from being a native of this land.

Before I unloaded my luggage in the barracks, I took a leisurely ride down the Avenue of Remembrance, which ran past the library, the chapel, and Durrell Hall on the west side of the parade ground. The Avenue was named in honor of the epigram from Ecclesiastes that appeared above the chapel door: "Remember Now Thy Creator in the Days of Thy Youth." When I first saw the unadorned architecture of the Institute, I thought it was unbelievedly ugly. But it had slowly grown on me.

The beauty of the campus, an acquired taste, certainly, lay in its stalwart understatement, its unapologetic capitulation to the supremacy of line over color, to the artistry of repetition, and the lyrics of a scrupulous unsenti- mental vision. The four barracks and all the main academic buildings on campus faced inward toward the parade ground, a vast luxurious greens- ward trimmed like the fairway of an exclusive golf course. The perfume of freshly mown grass hung over the campus throughout much of the year. Instruments of war decorated the four corners of the parade ground: a Sherman tank, a Marine landing craft, a Jupiter missile, and an Air Force Sabre jet. Significantly, all of these pretty decorations were obsolete and anachronistic when placed in reverent perpetuity on campus. The campus looked as though a squad of thin, humorless colonels had designed it. At the Institute, there was no ostentation of curve, no vagueness of definition, no blurring of order. There was a perfect, almost heartbreaking, congruence to its furious orthodoxy. To an unromantic eye, the Institute had the look of a Spanish prison or a fortress beleaguered not by an invading force but by the more threatening anarchy of the twentieth century buzzing insensately outside the Gates of Legrand.

It always struck me as odd that the Institute was one of the leading tourist attractions in Charleston. Every Friday afternoon, the two thousand members of the Corps of Cadets would march in a full-dress parade for the edification of both the tourists and the natives. There was always something imponderably beautiful in the anachronism, in the synchronization of the regiment, in the flashing gold passage of the Corps past the reviewing stand in a ceremony that was a direct throwback to the times when Napoleonic troops strutted for their emperor.

Ever since the school had been founded in 1842, after a slave insurrection, the Corps had marched on Fridays in Charleston, except on the Friday following that celebrated moment when cadets from the Institute had opened fire on the Star of the East, a Northern supply ship trying to deliver supplies to the beleaguered garrison at Fort Sumter. Historians credited those cadets with the first shots in the War Between the States. It was the proudest moment in the history of the school, endlessly appreciated and extolled as the definitive existential moment in its past. Patriotism was an alexin of the blood at the Institute, and we, her sons, would march singing and eager into every battle with the name of the Institute on our lips. There was something lyric and terrible in the fey mindlessness of Southern boys, something dreary and exquisite...

|

|

| View all 8 comments |

Boston Globe (MSL quote), USA

<2007-01-05 00:00>

God preserve Pat Conroy. |

Houston Post (MSL quote), USA

<2007-01-05 00:00>

Seldom have I encountered an author who puts words together so well - reading Conroy is like watching Michelangelo paint the Sistine Chapel. |

Washington Star (MSL quote), USA

<2007-01-05 00:00>

A work of enormous power, passion, humor, and wisdom. It sweeps the reader along on a great tide of honest, throbbing emotion. It is the work of a writer with a large, brave heart. |

Cynthia Robertson (MSL quote), USA

<2007-01-05 00:00>

Aspiring novelist and basketball player, Will McLean, finds himself a college student at the Carolina Military Institute (The Citadel - thinly disguised). Will was not interested in the military, but he promises his dying father that he will attend his alma mater. Will doesn't exactly excel in military studies, but he's a decent student, an athlete, and his professors and peers recognize him for his integrity and his sense of fairness. Still, this is not an easy time to be a student in a military academy - especially in the South. The Viet Nam War was raging, the military was unpopular and desegregation was knocking on the doors of Southern schools. The Fourth Class system is brutal at best, and most cadets will look on their freshman year and Hell Night as living nightmares. There are also rumors of a powerful and clandestine group of Institute students and alumni called The Ten. While nothing has come forward to prove their existence, the possibility of such a group casts a cloud over the Corps of Cadets.

Will and his roommates have survived the trials and tribulations of their underclassmen years. But circumstances change very rapidly. The first black student enrolls at the Institute and Will is asked to be a secret mentor to Cadet Tom Pearce. It quickly becomes apparent that a group of cadets is trying to run Pearce out of the Institute. Will steps in to intervene, and he discovers a truth so horrendous that this knowledge can bring down the Institute. It also makes Will and his roommates targets. Not only is their graduation now in jeopardy, but their lives are also in danger.

Conroy is a master wordsmith, and I find myself reading his sentences over and over again. It's comparable to taking a bite of a decadent dessert, and rolling it around on your tongue to savor every forkful. His descriptions are priceless, his characters well fleshed out, and the plot will have you marathon reading to finish this 498-page book. I especially loved his observations about Charleston and the low country. Conroy also deals with timeless and universal issues. They include the struggles of a young boy growing into manhood and how difficult it is to stand up for your beliefs. Also, how those that love you can cause the worst hurt, and how those you think are loyal friends can betray you in a heartbeat. Conroy dwells on how it is possible to love and hate something at the same time (in this case, the Institute), and how the righteous don't always prevail. And while things might turn out in the end, they might not turn out the way you envision them.

The one bad thing about Pat Conroy is that he is not one of those "serial" bestsellers who produce a book every year-whether they have anything to say or not. While we often have to wait years between books, Conroy's works are definitely worth the wait. Also, after reading The Lords of Discipline, I suggest picking up his nonfiction work, My Losing Season. Detailing his senior year playing basketball for The Citadel, Conroy will reveal how much of The Lords of Discipline is autographical. |

View all 8 comments |

|

|

|

|