|

|

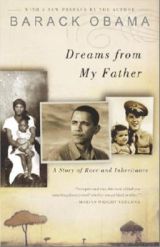

Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance (Paperback)

by Barack Obama

| Category:

African American, Personal achievement, Memoir, Autobiography |

| Market price: ¥ 168.00

MSL price:

¥ 148.00

[ Shop incentives ]

|

| Stock:

Pre-order item, lead time 3-7 weeks upon payment [ COD term does not apply to pre-order items ] |

MSL rating:

Good for Gifts Good for Gifts |

| MSL Pointer Review:

A powerful account of Senator Obama's search for his roots and identity as a black American. Highest recommendation! |

| If you want us to help you with the right titles you're looking for, or to make reading recommendations based on your needs, please contact our consultants. |

Detail |

Author |

Description |

Excerpt |

Reviews |

|

|

|

Author: Barack Obama

Publisher: Three Rivers Press; Reprint edition

Pub. in: August, 2004

ISBN: 1400082773

Pages: 480

Measurements: 8.2 x 5 x 1 inches

Origin of product: USA

Order code: BA00266

Other information: ISBN-13: 978-1400082773

|

|

Rate this product:

|

|

- Awards & Credential -

From the #1 New York Times Bestseller The Audacity of Hope, this compelling memoir is a classic in its own right ranking #29 in books out millions on Amazon.com as of January 18, 2007. |

|

- MSL Picks -

Barack Obama was of an interracial marriage. Most of us remember, until 1967, many children in interracial marriages, like those in gay households today, were deprived of equal rights under the laws. Yet, few recall that Albino Luciani (later to become John Paul I) led the same struggle in Italy.

As a bishop, in Jan 1965, he told the Italian Parliament, "We are speaking here of the pursuit of happiness - the inalienable right of free men to grow up and fall in love with whomever God deems one fall in love with, together with the sacred duty to provide for the economic and loving support of children so that they too can enjoy the pursuit of happiness. . . Marriage is a God-given individual right and cannot be infringed upon by the majority. The state cannot tell its citizens who they can or cannot marry less we cease to be a free society... " I got that out of the only existing biography of the 33 day pope, Lucien Gregoire's "Murder in the Vatican; The Revolutionary Life of John Paul". In the same session, Luciani won the right for single persons, including homosexuals, to adopt children to help care for Italy's huge orphan population.

Like Luciani, Obama is a man of towering eloquence, and it is that which will eventually bring him to the top. In the short run, his writings and his deeds will pave the way. Yet, it is his heritage, perhaps, more than anything else that makes him understanding of the true meaning of democracy, "Democracy which finds its strength in rule by the people, can only realize its purpose, its sacred duty to society, in preserving the basic human rights of its loneliest individual." (Albino Luciani, Christian Democratic Party Convention, August 1963).

(From quoting John Marshall, USA)

Target readers:

General readers, but we highly recommend the book to all aspiring young people, who might be inspired by the story of Senator Obama.

|

|

- Better with -

Better with

The Autobiography of Malcolm X: As Told to Alex Haley (Mass Market Paperback)

:

|

|

Customers who bought this product also bought:

|

|

Barack Obama graduated from Harvard Law School in 1991, where he served as the first African-American president of the Harvard Law Review. He has worked as a community organizer, civil rights attorney, and law professor. Since 1997, he has represented parts of Chicago's South Side in the Illinois General Assembly, and he is currently the Democratic nominee to become the junior U.S. senator from Illinois. He lives in Chicago with his wife, Michelle, and daughters, Malia and Sasha.

|

|

From Publisher

In this lyrical, unsentimental, and compelling memoir, the son of a black African father and a white American mother searches for a workable meaning to his life as a black American. It begins in New York, where Barack Obama learns that his father - a figure he knows more as a myth than as a man - has been killed in a car accident. This sudden death inspires an emotional odyssey - first to a small town in Kansas, from which he retraces the migration of his mother's family to Hawaii, and then to Kenya, where he meets the African side of his family, confronts the bitter truth of his father's life, and at last reconciles his divided inheritance.

|

Preface to the 2004 Edition

Almost a decade has passed since this book was first published. As I mention in the original introduction, the opportunity to write the book came while I was in law school, the result of my election as the first African-American president of the Harvard Law Review. In the wake of some modest publicity, I received an advance from a publisher and went to work with the belief that the story of my family, and my efforts to understand that story, might speak in some way to the fissures of race that have characterized the American experience, as well as the fluid state of identity - the leaps through time, the collision of cultures - that mark our modern life.

Like most first-time authors, I was filled with hope and despair upon the book’s publication - hope that the book might succeed beyond my youthful dreams, despair that I had failed to say anything worth saying. The reality fell somewhere in between. The reviews were mildly favorable. People actually showed up at the readings my publisher arranged. The sales were underwhelming. And, after a few months, I went on with the business of my life, certain that my career as an author would be short-lived, but glad to have survived the process with my dignity more or less intact.

I had little time for reflection over the next ten years. I ran a voter registration project in the 1992 election cycle, began a civil rights practice, and started teaching constitutional law at the University of Chicago. My wife and I bought a house, were blessed with two gorgeous, healthy, and mischievous daughters, and struggled to pay the bills. When a seat in the state legislature opened up in 1996, some friends persuaded me to run for the office, and I won. I had been warned, before taking office, that state politics lacks the glamour of its Washington counterpart; one labors largely in obscurity, mostly on topics that mean a great deal to some but that the average man or woman on the street can safely ignore (the regulation of mobile homes, say, or the tax consequences of farm equipment depreciation). Nonetheless, I found the work satisfying, mostly because the scale of state politics allows for concrete results - an expansion of health insurance for poor children, or a reform of laws that send innocent men to death row - within a meaningful time frame. And too, because within the capitol building of a big, industrial state, one sees every day the face of a nation in constant conversation: inner-city mothers and corn and bean farmers, immigrant day laborers alongside suburban investment bankers - all jostling to be heard, all ready to tell their stories.

A few months ago, I won the Democratic nomination for a seat as the U.S. senator from Illinois. It was a difficult race, in a crowded field of well-funded, skilled, and prominent candidates; without organizational backing or personal wealth, a black man with a funny name, I was considered a long shot. And so, when I won a majority of the votes in the Democratic primary, winning in white areas as well as black, in the suburbs as well as Chicago, the reaction that followed echoed the response to my election to the Law Review. Mainstream commentators expressed surprise and genuine hope that my victory signaled a broader change in our racial politics. Within the black community, there was a sense of pride regarding my accomplishment, a pride mingled with frustration that fifty years after Brown v. Board of Education and forty years after the passage of the Voting Rights Act, we should still be celebrating the possibility (and only the possibility, for I have a tough general election coming up) that I might be the sole African American - and only the third since Reconstruction - to serve in the Senate. My family, friends, and I were mildly bewildered by the attention, and constantly aware of the gulf between the hard sheen of media reports and the messy, mundane realities of life as it is truly lived.

Just as that spate of publicity prompted my publisher’s interest a decade ago, so has this fresh round of news clippings encouraged the book’s re-publication. For the first time in many years, I’ve pulled out a copy and read a few chapters to see how much my voice may have changed over time. I confess to wincing every so often at a poorly chosen word, a mangled sentence, an expression of emotion that seems indulgent or overly practiced. I have the urge to cut the book by fifty pages or so, possessed as I am with a keener appreciation for brevity. I cannot honestly say, however, that the voice in this book is not mine - that I would tell the story much differently today than I did ten years ago, even if certain passages have proven to be inconvenient politically, the grist for pundit commentary and opposition research.

What has changed, of course, dramatically, decisively, is the context in which the book might now be read. I began writing against a backdrop of Silicon Valley and a booming stock market; the collapse of the Berlin Wall; Mandela - in slow, sturdy steps - emerging from prison to lead a country; the signing of peace accords in Oslo. Domestically, our cultural debates - around guns and abortion and rap lyrics - seemed so fierce precisely because Bill Clinton’s Third Way, a scaled-back welfare state without grand ambition but without sharp edges, seemed to describe a broad, underlying consensus on bread-and-butter issues, a consensus to which even George W. Bush’s first campaign, with its “compassionate conservatism,” would have to give a nod. Internationally, writers announced the end of history, the ascendance of free markets and liberal democracy, the replacement of old hatreds and wars between nations with virtual communities and battles for market share.

And then, on September 11, 2001, the world fractured.

It’s beyond my skill as a writer to capture that day, and the days that would follow - the planes, like specters, vanishing into steel and glass; the slow-motion cascade of the towers crumbling into themselves; the ash-covered figures wandering the streets; the anguish and the fear. Nor do I pretend to understand the stark nihilism that drove the terrorists that day and that drives their brethren still. My powers of empathy, my ability to reach into another’s heart, cannot penetrate the blank stares of those who would murder innocents with abstract, serene satisfaction.

What I do know is that history returned that day with a vengeance; that, in fact, as Faulkner reminds us, the past is never dead and buried - it isn’t even past. This collective history, this past, directly touches my own. Not merely because the bombs of Al Qaeda have marked, with an eerie precision, some of the landscapes of my life - the buildings and roads and faces of Nairobi, Bali, Manhattan; not merely because, as a consequence of 9/11, my name is an irresistible target of mocking websites from overzealous Republican operatives. But also because the underlying struggle - between worlds of plenty and worlds of want; between the modern and the ancient; between those who embrace our teeming, colliding, irksome diversity, while still insisting on a set of values that binds us together, and those who would seek, under whatever flag or slogan or sacred text, a certainty and simplification that justifies cruelty toward those not like us - is the struggle set forth, on a miniature scale, in this book.

I know, I have seen, the desperation and disorder of the powerless: how it twists the lives of children on the streets of Jakarta or Nairobi in much the same way as it does the lives of children on Chicago’s South Side, how narrow the path is for them between humiliation and untrammeled fury, how easily they slip into violence and despair. I know that the response of the powerful to this disorder - alternating as it does between a dull complacency and, when the disorder spills out of its proscribed confines, a steady, unthinking application of force, of longer prison sentences and more sophisticated military hardware - is inadequate to the task. I know that the hardening of lines, the embrace of fundamentalism and tribe, dooms us all.

And so what was a more interior, intimate effort on my part, to understand this struggle and to find my place in it, has converged with a broader public debate, a debate in which I am professionally engaged, one that will shape our lives and the lives of our children for many years to come.

The policy implications of all this are a topic for another book. Let me end instead on a more personal note. Most of the characters in this book remain a part of my life, albeit in varying degrees - a function of work, children, geography, and turns of fate.

The exception is my mother, whom we lost, with a brutal swiftness, to cancer a few months after this book was published.

She had spent the previous ten years doing what she loved. She traveled the world, working in the distant villages of Asia and Africa, helping women buy a sewing machine or a milk cow or an education that might give them a foothold in the world’s economy. She gathered friends from high and low, took long walks, stared at the moon, and foraged through the local markets of Delhi or Marrakesh for some trifle, a scarf or stone carving that would make her laugh or please the eye. She wrote reports, read novels, pestered her children, and dreamed of grandchildren.

We saw each other frequently, our bond unbroken. During the writing of this book, she would read the drafts, correcting stories that I had misunderstood, careful not to comment on my characterizations of her but quick to explain or defend the less flattering aspects of my father’s character. She managed her illness with grace and good humor, and she helped my sister and me push on with our lives, despite our dread, our denials, our sudden constrictions of the heart...

|

|

| View all 10 comments |

Washington Post Book World (MSL quote), USA

<2007-01-21 00:00>

Fluidly, calmly, insightfully, Obama guides us straight to the intersection of the most serious questions of identity, class, and race. |

Scott Turow (MSL quote), USA

<2007-01-21 00:00>

Beautifully crafted... moving and candid... this book belongs on the shelf beside works like James McBride’s The Color of Water and Gregory Howard Williams’s Life on the Color Line as a tale of living astride America’s racial categories. |

Alex Kotlowitz (Author of There Are No Children Here) (MSL quote), USA

<2007-01-21 00:00>

Obama's writing is incisive yet forgiving. This is a book worth savoring. |

J. Krueger (MSL quote), USA

<2007-01-21 00:00>

I read this for one of my reading groups. Being the non-political person that I am, I was completely unaware of who this person is, but my very political girlfriend filled me in. Obama is currently a US Senator from Illinois and a hot guy in the Democratic party these days. After reading his memoir, I am a supporter. He has a fine sense of integrity and understanding about people though I fear that the political process in this country would kill that off in even the strongest individual.

In the early 90s, Obama was studying law at Harvard and became the first black man to be elected as President of the Harvard Law Review. The publicity engendered by this event brought him a publishing offer, so he wrote this story of his life up to that point. After winning the seat in the US Senate, the book was republished.

Obama's mother was a white woman from Kansas, whose family moved to Hawaii when she was a teenager. There at the University of Hawaii, she met an African student from Kenya. They married and had Barack in the early 60s. But the father left when Barack was only 2 years old, to get his PhD at Harvard because his scholarship money was not enough to support a wife and child. Before he could complete his degree, he was summoned back to Kenya by his government and the marriage dissolved due to time and distance.

So Barack was raised by his white mother and grandparents while his father took on the quality of a myth. When Barack was ten years old, his father came for a two week visit which only served to confuse Barack further. But he managed to complete high school and college, by which time he had decided to live as a black man.

After college, he went to Chicago to work as a community organizer in the ghettos of South Chicago and came face to face with the results of racism in a northern industrial city. Just before entering Harvard Law School, he finally traveled to Kenya and met his father's side of the family, finding at last the other half of his heritage.

It was a fascinating book, written in a novelist's style and hard to put down. It added much to my growing fund of knowledge about Blacks in this country, their African forebears, racism and the long slow climb of the Black race in America from slaves to full citizens of this country; a climb which is far from over.

I doubt that this country is ready to elect a Black President, but I am sure it will happen in my lifetime. If Obama can stay in politics and maintain the integrity he displays in his book, I would be glad to have him as President of the United States.

|

View all 10 comments |

|

|

|

|